By Andrew Ross

Photos courtesy of Davies Manor Association Research Assistant Kim Fleischhauer and Robert Jordan of Ole Miss Communications

The Forgotten Story of Julius Augustus Davies

The writer David Cohn may have pinpointed a figurative truth when he famously claimed the Mississippi Delta begins in the Peabody’s lobby. Literally, of course, he was about fifteen miles off. Head south from Memphis on Highway 61, and the Delta’s true starting point becomes readily apparent just over the state line at a spot where the roadway, after winding down lazily through the ancient Loess Hills, suddenly intersects with the northern-most crest of the Yazoo-Mississippi-Delta levee system.

Gaze out from here upon the region’s signature horizon of sprawling flatland and sky. I personally find this stretch of countryside a bit hypnotic. I think it’s the particular way the landscape morphs before one’s eyes—hills, flatland, levee, and river all colliding at once in the very shadows of South Memphis’s cityscape. There’s also something mesmerizing about the Loess Hills themselves. Formed during the last ice age from deposits of wind-blown silt, these hills, lined with kudzu-choked ravines and pockets of towering oaks, seem to hum with an energy that’s primordial and mysterious and not a little dark.

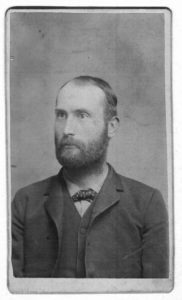

Such were the odd sorts of associations on my mind one recent afternoon as I dropped into Mississippi from Memphis and, almost immediately, pulled into the tiny town of Walls. I’d come to this place “where the Delta meets the bluff” to learn more about a long-forgotten resident named Julius Augustus Davies. Known simply as Gus to his family and friends, Davies lived and worked in Walls as an ophthalmologist in the late 1800s until his death in 1924. Along with practicing medicine, he became moderately wealthy purchasing cotton-rich land that he leased to African-American sharecroppers. But these weren’t the real reasons I’d become so interested in the man. What gripped me instead had to do with his intimate relationship with the North Delta itself—specifically, his compulsion to unearth the land’s oldest human secrets.

Such were the odd sorts of associations on my mind one recent afternoon as I dropped into Mississippi from Memphis and, almost immediately, pulled into the tiny town of Walls. I’d come to this place “where the Delta meets the bluff” to learn more about a long-forgotten resident named Julius Augustus Davies. Known simply as Gus to his family and friends, Davies lived and worked in Walls as an ophthalmologist in the late 1800s until his death in 1924. Along with practicing medicine, he became moderately wealthy purchasing cotton-rich land that he leased to African-American sharecroppers. But these weren’t the real reasons I’d become so interested in the man. What gripped me instead had to do with his intimate relationship with the North Delta itself—specifically, his compulsion to unearth the land’s oldest human secrets.

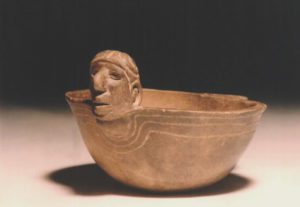

Beyond simple curiosity, it is unclear what exactly drove Dr. Davies to spend a good chunk of his adult life digging in the dirt around Walls for prehistoric artifacts. It certainly wasn’t money; he did not sell the Mississippian Period materials that he unearthed, and, just before his death in 1924, donated the entirety of his collection to the University of Mississippi. Public recognition wasn’t a factor either: Never did he publish or formally catalogue his finds. Instead, Gus, a lifelong bachelor, chose to live alone with his discoveries in the manner of a hoarder, haphazardly stacking ancient pottery and tools (and yes, even human remains) in every available space of his simple, four-room home. Eventually, according to one account, all that remained were “narrow pathways…for essential routes.” But regardless of Gus’s eccentricities, the impact this unassuming doctor had on the Mid-South’s archeological record is undeniable: today the collection that bears his name is considered one of the largest and most intact assemblages of Mississippian vessels ever found.

In the decades following Ole Miss’s acquisition of the nearly 400 objects in the Davies Collection, a handful of scholars and students studied the vessels’ exceptional iconography. Occasionally, the university collaborated with small museums on exhibits. Mostly though, the collection remained in storage inside the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. That’s been changing in recent years. In 2016, an exhibit at Ole Miss’s Barnard Observatory significantly raised the profile of the collection. The Davies Collection: Mississippian Iconographic Vessels, was so well received it led to a follow-up display in the campus library. Two years later, another sample of the collection’s effigy vessels was loaned to the Historic New Orleans Collection. Going forward, plans for a new exhibit are in the works with a certain art museum on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. For all the renewed interest in the artifacts themselves, however, the man responsible for the collection’s existence continues to remain an enigma. With the exception of a brief 1991 article in Mississippi Archeology and a few scattered references in books, nothing at all has been written on Dr. Davies. As the authors of the above-mentioned article correctly noted, Gus was a “most unusual collector” whose “fame, unfortunately, is not commensurate with his contribution.”

In the decades following Ole Miss’s acquisition of the nearly 400 objects in the Davies Collection, a handful of scholars and students studied the vessels’ exceptional iconography. Occasionally, the university collaborated with small museums on exhibits. Mostly though, the collection remained in storage inside the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. That’s been changing in recent years. In 2016, an exhibit at Ole Miss’s Barnard Observatory significantly raised the profile of the collection. The Davies Collection: Mississippian Iconographic Vessels, was so well received it led to a follow-up display in the campus library. Two years later, another sample of the collection’s effigy vessels was loaned to the Historic New Orleans Collection. Going forward, plans for a new exhibit are in the works with a certain art museum on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. For all the renewed interest in the artifacts themselves, however, the man responsible for the collection’s existence continues to remain an enigma. With the exception of a brief 1991 article in Mississippi Archeology and a few scattered references in books, nothing at all has been written on Dr. Davies. As the authors of the above-mentioned article correctly noted, Gus was a “most unusual collector” whose “fame, unfortunately, is not commensurate with his contribution.”

Julius Augustus Davies was born in 1855 on a slave-powered cotton and livestock plantation some twenty miles east of Memphis. Though his parents were economically secure, his childhood was far from carefree. Gus’s mother, Almeda, died of unknown causes when he was four. A few years later, his father, James, headed off to the Civil War as a Confederate infantry soldier, leaving Gus and his younger brother Will in the care of an uncle and aunt. Although James Davies would survive more than three years of harrowing combat, he returned home a psychologically tortured man. Verbal abuse and threats of violence toward his new wife, Pauline (Almeda’s sister as it happens), became common. So too did talk of suicide. It all came to a head one afternoon in the spring of 1867, when James, in a “fit of excitement,” pulled a loaded gun on Pauline as she was sitting on the porch of their home. With the help of one of her step-sons (the accounts don’t clarify but it was most likely Gus), Pauline managed to wrestle the gun away. Minutes later, James pulled a razor from his pocket, and, in “desperation of his frenzy,” partially slit his own throat. A neighbor’s last minute intervention was all that prevented James from finishing the job.

Julius Augustus Davies was born in 1855 on a slave-powered cotton and livestock plantation some twenty miles east of Memphis. Though his parents were economically secure, his childhood was far from carefree. Gus’s mother, Almeda, died of unknown causes when he was four. A few years later, his father, James, headed off to the Civil War as a Confederate infantry soldier, leaving Gus and his younger brother Will in the care of an uncle and aunt. Although James Davies would survive more than three years of harrowing combat, he returned home a psychologically tortured man. Verbal abuse and threats of violence toward his new wife, Pauline (Almeda’s sister as it happens), became common. So too did talk of suicide. It all came to a head one afternoon in the spring of 1867, when James, in a “fit of excitement,” pulled a loaded gun on Pauline as she was sitting on the porch of their home. With the help of one of her step-sons (the accounts don’t clarify but it was most likely Gus), Pauline managed to wrestle the gun away. Minutes later, James pulled a razor from his pocket, and, in “desperation of his frenzy,” partially slit his own throat. A neighbor’s last minute intervention was all that prevented James from finishing the job.

One can only guess at the emotional scars Gus and Will suffered from that traumatic event (There were others too, according to divorce proceedings filed by Gus’s mother-in-law). While James managed to live on until 1904, he continued to deal with what we’d now call post traumatic stress disorder. The experience of living with a mentally disturbed father probably impacted Gus’s and Will’s decision to pursue careers in medicine. The brothers studied under a local doctor through their teens then earned medical degrees from Vanderbilt University—Will in 1878 and Gus the following year. Both also pursued post-graduate work at New York University. Afterwards, Will moved home to help care for his father and set up practice as a general doctor. Gus, however, was ready to break out on his own. He briefly practiced in Memphis before permanently moving to Walls, known at the time as Alpika.

Nothing Davies left behind in his business records or correspondence indicates exactly when he began to dig around Walls nor how early in life he’d developed his interest in prehistory. According to an account from one of his younger cousins, Gus collected Native American artifacts even as child—a claim that’s not unlikely considering the Chickasaw hunting trails that had once passed through his family’s land. Regardless how it happened, by at least the early 1900s, he’d become an active digger and collector, focusing much of his attention on a particular Mississippian burial site just a mile or so from his home in Walls. Though the “Walls site” burial fields would later be destroyed by levee construction, the nearby Edgefield Mounds are designated today as part of the Mississippi Mound Trail.

The excavations that Gus carried out at the Walls site relied heavily on the physical labor of Mose Frazier, a sharecropper who leased a portion of Davies’ land. Another local sharecropper whose name has been lost is also believed to have been a member of Gus’s “field crew.” The particular digging method they employed, known as “probe and pit,” would be considered crude by modern standards. But in their day, before professional archeological practices were commonplace, such a technique was accepted, if not considered innovative. The key tool was a steel rod that Gus special ordered from a machine shop in Memphis. Roughly four and a half feet long by 3/16 of an inch in diameter, one end of the rod attached to a wooden handle while the other end tapered into a sharp point that could easily penetrate the soft Delta soil. Oftentimes, Gus would select a particular section of ground, then head off on his day’s rounds, leaving Mose to probe until he made contact with objects that felt promising enough to excavate. Returning in the afternoon, Davies would examine the discoveries, determining what to keep and what to discard.

The excavations that Gus carried out at the Walls site relied heavily on the physical labor of Mose Frazier, a sharecropper who leased a portion of Davies’ land. Another local sharecropper whose name has been lost is also believed to have been a member of Gus’s “field crew.” The particular digging method they employed, known as “probe and pit,” would be considered crude by modern standards. But in their day, before professional archeological practices were commonplace, such a technique was accepted, if not considered innovative. The key tool was a steel rod that Gus special ordered from a machine shop in Memphis. Roughly four and a half feet long by 3/16 of an inch in diameter, one end of the rod attached to a wooden handle while the other end tapered into a sharp point that could easily penetrate the soft Delta soil. Oftentimes, Gus would select a particular section of ground, then head off on his day’s rounds, leaving Mose to probe until he made contact with objects that felt promising enough to excavate. Returning in the afternoon, Davies would examine the discoveries, determining what to keep and what to discard.

Judging by first-hand accounts and a few surviving pictures of his pottery-cluttered home, Davies did not discard much. Strangely though, his desire to amass does not seem to have translated to reverence for the artifacts. According to Dr. Calvin Brown, an Ole Miss professor and fellow collector who befriended Gus toward the end of his life, Davies “never looked at [his finds] once he had found a place for them on the floor.” Whatever Brown may have thought about such habits, it did not hinder the mutually-beneficial relationship he and Davies formed. It was through Brown’s encouragement that Davies decided to gift his collection to Ole Miss. It would also be through Brown that Davies’s name, albeit posthumously, received wider recognition. Just a few years after Gus’s death, Brown published Archeology of Mississippi. The book, which is still considered a classic, included a sizable section on the artifacts from Walls.

Nearly all of the artifacts that Gus and Mose unearthed from the Walls site in the early twentieth century were grave goods that had been buried sometime between 1200-1400 AD. These years were the apex of the Mississippian Period, a time when thriving chiefdoms of indigenous people could be found up and down the Mississippi Valley. The people living in these chiefdoms were masters of large- scale corn cultivation. They built elaborate earthen mounds and established trade networks that extended as far as the Rockies and Great Lakes. They also had distinct religious beliefs. Their most fundamental religious concept was that of the “cosmos,” a three- tiered system of worlds (Above, Middle, and Below) populated by a combination of deities, humans, animals, and supernatural half- human, half-animal creatures among other anomalous beings. For the Mississippians, the interactions between these specific entities and worlds represented notions of order and security on one end of the spectrum and chaos and uncertainty on the other. Sadly, the latter notions would soon come to dominate their civilization after the fateful arrival of the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1541.

Today, beyond surviving physical artifacts and the remnants of mounds they left behind, all evidence of this once mighty civilization has vanished. And yet, that’s not entirely true—not really. Recently, when I spoke with the Ole Miss anthropology professors Tony Boudreaux and Maureen Meyers, it became apparent that the Mississippians’ more intangible contributions—things like their symbols, rituals, and, yes, feelings about the world they inhabited—are quite alive in modern research. Objects from this lost civilization, in other words, even ones that were relatively ordinary in their design and purpose, are much more than objects in and of themselves; oftentimes, they are direct portals into deeper layers of human understanding.

When it comes to the Davies Collection in particular, Boudreaux and Meyers make one thing clear: What they have in their department’s possession is far from ordinary. In Meyer’s view, the collection is the “shining star” of the university’s overall collection of 1,300 boxes of prehistoric materials. Along with the hundreds of pieces of pottery, the collection features specialized tools and domestic items, including mortars, pipes, ear-plugs, gorgets, discoidals, and knives. “I’ve never seen a collection that’s this size and in this good shape,” Meyers says. “And it’s passed down through other archeologists over how many years.”

Yet that’s not all that makes the Davies Collection so special. Quite a few of the vessels feature complex anthropological clues that appear in the form of iconographic engravings and effigy figures. The engravings and designs are “extraordinary works of art,” says Boudreaux. Furthermore, they are all united by a particular religious theme: the Below World of the Cosmos. It’s on this point that the professors become especially animated, describing how vessels shaped like fish and frogs and snakes all connect to Mississippian beliefs in the underworld. “The rough comparison might be a case where you had a whole Christian pottery collection that only had symbols of the pearly gates,” she explains. “It’s clearly tied to a specific belief system.” Meyers notes that one of the most oft-repeated engravings depicts the Uktena—a mythical monster that lived in the water but was actually associated with all three worlds. “It has the wings of a bird, so it’s in the upper world, and horns of a deer, which represent this world, and scales of a snake for the underworld.” Myers pauses before adding a few words of semi-serious caution. “You’re not supposed to look directly at it,” she says, “or bad things can happen.”

4 thoughts on “A Most Unusual Collector”

What a wonderfully comprehensive article! I enjoyed it immensely! So glad that technical verbiage was easy to understand. So fascinated to find this personality in our backyard.

It’s okay to look at most of the Ukteena. The specific part you have to avoid looking at is the red spot that glows like a red jewel on the center of its forehead—just above the nose bridge. That is when really bad things happen to you—like what happens after looking Gorgon Medusa in the face. In the Appalachian Mountain chain, the Ukteena lived far, far, far, far deep into the forest.

Today the only people who might encounter this rare mythical creature are the people who walk the Appalachian Trail. I wonder if the Ukteena mythology served as a verbal or visual warning sign to keep ancient people from getting off the major trail systems in the Southeast and getting lost in the deepest portions of the forest. Some people probably did occasionally get lost, and they all turned up dead from hypothermia, falls, animal maulings, and other such deep woodlands incidents. Naturally, these deaths were attributed to encounters with an Ukteena. As always with humans, anything bad that happens to a person requires some sort of explanation that fits in with the local culture and its belief system. Feel free to visit me any time at my archaeology website and blog. Just click on the following safe links:

https://archaeologyinoakridge.wordpress.com/

https://contextintn.wordpress.com/

I knew an old guy like Davies in Boulder, Colorado – an old guy named Bill. Bill’s grandfather had taught him where to find arrowheads in and around New Mexico and Southern Colorado. Like Davies, Bill collected thousands of arrowheads, pottery and a few baskets between 1920 and 1950 only to put them into a little study off of the dining room and, basically, never to be seen again. I would stop by once a year or so and spend as much time as I could looking at as many pieces as I could before I was shooed out of the room. I heard that, when he died, the whole lot was sold at an “estate sale” to anyone that had a couple of dollars for arrowheads and $50 or $60 dollars for pots. Have wished many times that I was there the day of the sale.

This story brings back many memories. My guess was that Bill enjoyed the hunt more than the collection.

Excellent ! Thank You .