By CAYMAN CLEVENGER

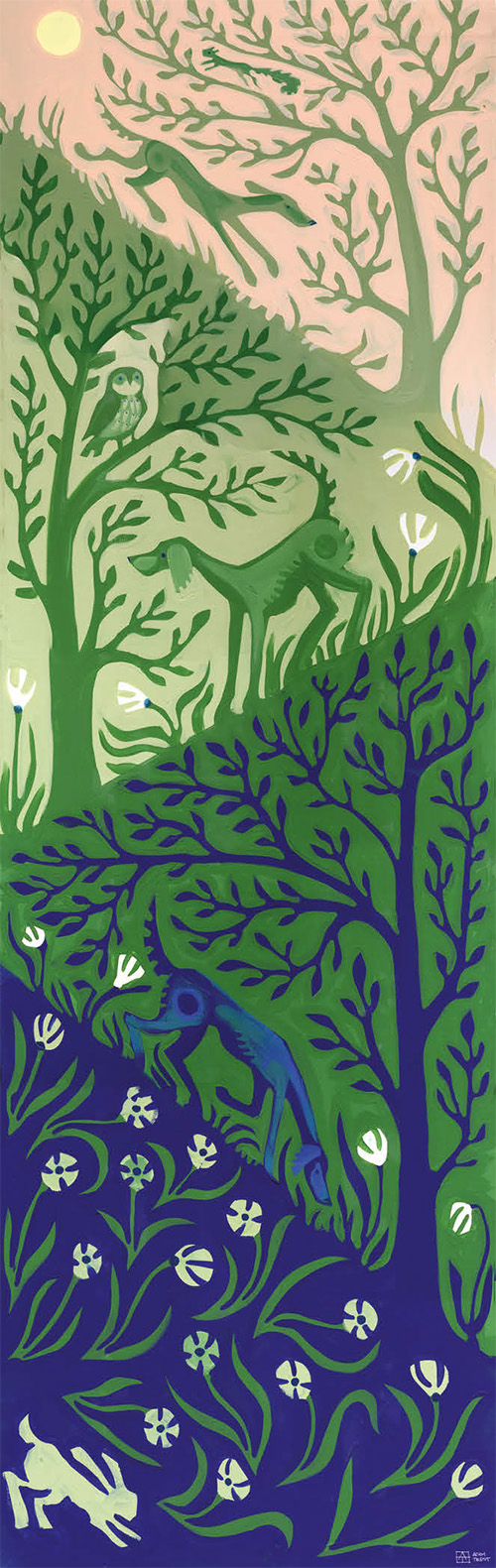

Take one step inside the historic heart of downtown Laurel, Mississippi, and Adam Trest’s studio feels instantly alive—a living aviary stitched together in paint. A flash of a fishing net cuts through the air, a great blue heron rises from a painted marsh with slow, deliberate grace, and a scarlet cardinal perches mid-canvas a signal from Mother Nature of quiet beauty and grace. Overhead, a pelican wheels in wide, confident arcs; from a thicket of trees, a singular deer emerges.

Even the stillness has its own pulse, a fox curled deep in its den, keeping quiet watch over the landscape. Here, nature doesn’t just appear on canvas; it sings and it tells a story. Every brushstroke is a note in a Southern symphony, each one meant to stir memory and tether the viewer to a place that feels like home.

For Trest, each of these still compositions are living stories: threads of the Delta and the Deep South, woven to transfix, transport, and keep the past alive. Nature abounds in vibrant brushstrokes, each stroke part of a visual ballet that invokes a childlike sense of wonder and taps into the universal language of shared memory. These images are far more than decoration. They are the threads of the Southern story, woven in a way that both transfixes and transports his audience to cherished moments of the past.

Trest, an esteemed visual storyteller and a New York Times bestselling illustrator, demonstrates a deep understanding of Walter Anderson’s artistic language, yet his creations are distinguished by a unique style, exceptional quality, and personal choice of medium. His classical training, coupled with an innovative approach to color, positions him prominently in the realm of contemporary Southern art.

Though his ties to Mississippi run deep, Trest spent his childhood across the Gulf South, steeped in nature and immersed in Southern imagery—from the marshes of Louisiana to the piney woods of Laurel. Born in Lafayette, Louisiana, he followed his father’s oil field career to Houma and Texas before his family returned to Laurel when he was nine. Art was an enduring companion. His mother, a language arts teacher, encouraged creativity, and the Lauren Rogers Museum became his playground. He recalls impromptu field trips and afternoons playing tag around a Rodin sculpture—early encounters that seeded his life-long fascination with art and storytelling.

“I had this magical Southern childhood, like it was out of a novel,” Trest shares. “Growing up, there was a fox den 200 feet behind our back door. As a child, it’s magical to see a fox running in a field behind your house. Now, when I see a fox, I know it’s going to be a good day. In my work, I seek to capture that magical feeling.”

Mississippi Lost + Found

Trest’s deep connection to the state came into focus with his first solo museum exhibition at The MAX in Meridian: Mississippi Lost + Found. The show celebrated each of Mississippi’s distinct regions—Tombigbee Hills, Coastal Plains, Black Prairie, Piney Woods, and, of course, the Delta. Each 30×40 canvas shared the same palette and proportions, but the imagery reflected the unique landscape and inhabitants of each place.

“Each of the pieces celebrated the landscape of the region with the flora and fauna that’s found there, specifically looking at threatened species. The Delta has so many birds, and there’s a catfish in the image. But the landscape itself, it’s so different. Painting the Tombigbee Hills, there’s elevation and dense trees. With the Delta, it’s about simplicity. It was probably the most relatable piece in the series, because so many people have such affection for the Delta.”

That affection comes through in his work—not just in the obvious symbols like catfish, ducks, and deer, but in the unspoken atmosphere of open fields, distant tree lines, and skies that seem to go on forever. “The Delta is a place where the horizon itself becomes a kind of subject,” he says. “There’s a purity in that simplicity.”

Folk Traditions and The Great Outdoors

Hunting, fishing, and outdoor traditions of the Delta find their way into Trest’s work as cultural touchstones. “When you look at traditional folk art, you’re often looking at traditions passed down from generation to generation,” he explains. “Here in Mississippi, being outdoors, whether it’s hunting, fishing, or just being present with the land, is one of those traditions.”

Trest recalls going with his father to “let the fox dogs run,” and listening to them all night. “You knew which dog was chasing what. I’m not a big hunter myself,” he laughs, “but I appreciate that it’s part of who we are.”

His appreciation shows up in his paintings as layered allegory. “Yes, on the surface, a dog chasing a rabbit is simple,” he says. “But start thinking about it—what are the things you pursue? What is your rabbit? That’s the beauty of folk inspiration—it’s simple enough to be understood at a glance, but it holds deeper meaning the more you sit with it.” A fox, for example, is shorthand for Trest to express a hope that its going to be a good day, a dog added to a piece with a Fox is shorthand for “pursue a good day.” A callback to the sense of mystery and wonder Trest felt as a child when he encouraged a fox in his childhood back yard.

His “Nearly Free” piece, with dogs in mid-chase, and his paintings of his father’s yard, light cascading across the grass, patterns found in everyday nature, capture both the thrill of the chase and the peace of home. “Nature and the outdoors go hand-in-hand with the way I paint,” he says. “You could pull any image I’ve worked on and find that influence.”

Process and Medium

Though his early career included traditional portraiture and house paintings, Trest’s work has evolved into dynamic, symbolic expressions alive with pattern and color. His primary medium is acrylic on canvas or board, sometimes combined with ink on paper. His marks of translucency and layering reflect his training under watercolorist Brent Funderburk at Mississippi State University.

His process begins not on the canvas, but in leather-bound sketchbooks. “I never sketch on the canvas,” he says. “With three kids, my studio time is precious. I plan compositions in my sketchbook—color palettes, swatches, detailed drawings—so when I get into the studio, I’m ready to go.”

This disciplined approach doesn’t stifle creativity; it ensures that when the brush meets the canvas, the work flows freely. “Original artwork should be experimentation,” he says. “Every piece should push you into something new.”

Storytelling Across Mediums

Trest’s storytelling extends beyond fine art into wallpaper, fabric, tile, stationery, and even needlepoint and quilting design. His ability to adapt his work into different forms has expanded his audience without losing authenticity. “Every way I use my work is about connecting with the stories and memories people hold dear,” he says.

His collaboration with Erin and Ben Napier of HGTV’s Home Town introduced his art to a national audience. They featured his work on the show, renovated a home for him, built a pool and cabana using his Lili encaustic tiles, and even used his designs for wallpaper in his current home. His work as illustrator for The Lantern House with Erin Napier became a New York Times bestseller, proving his imagery resonates with all ages.

Looking Ahead: Folk

Trest’s next major collection will explore the idea of “folk” through place: Coast Folk, Bayou Folk,City Folk, and Country Folk. Each series will examine the relationship between people and their landscapes.

“For the Bayou pieces, I’m excited about the contrast between New Orleans and Houma—city bayou versus rural bayou,” he says. “I’m playing with how cypress forests and architecture both carry weight and how they form a sense of place. The beauty of being in a cathedral of cypress trees can altogether feel like standing in front of the St. Louis Cathedral.”

That blending of natural and human-made forms, and of cultural and ecological heritage, is at the heart of what makes Trest’s work resonate, especially in the Delta. His paintings are, in the truest sense, Mississippi stories, rooted in place, steeped in memory, and alive with the symbols of a landscape that has shaped generations.

Trest’s work can be found at Caron Gallery in Laurel or Tupelo, Orleans Gallery in New Orleans, or at adamtrest.com. And, for those who know how to look, in the open fields and wooded edges of the Mississippi Delta—where a fox may be running, a dog may be in pursuit, and the horizon always invites you to follow.