By JIM BEAUGEZ

Webb Wilder celebrates the music of his native Mississippi from behind the mic—on stage, in the recording studio, and over the airwaves

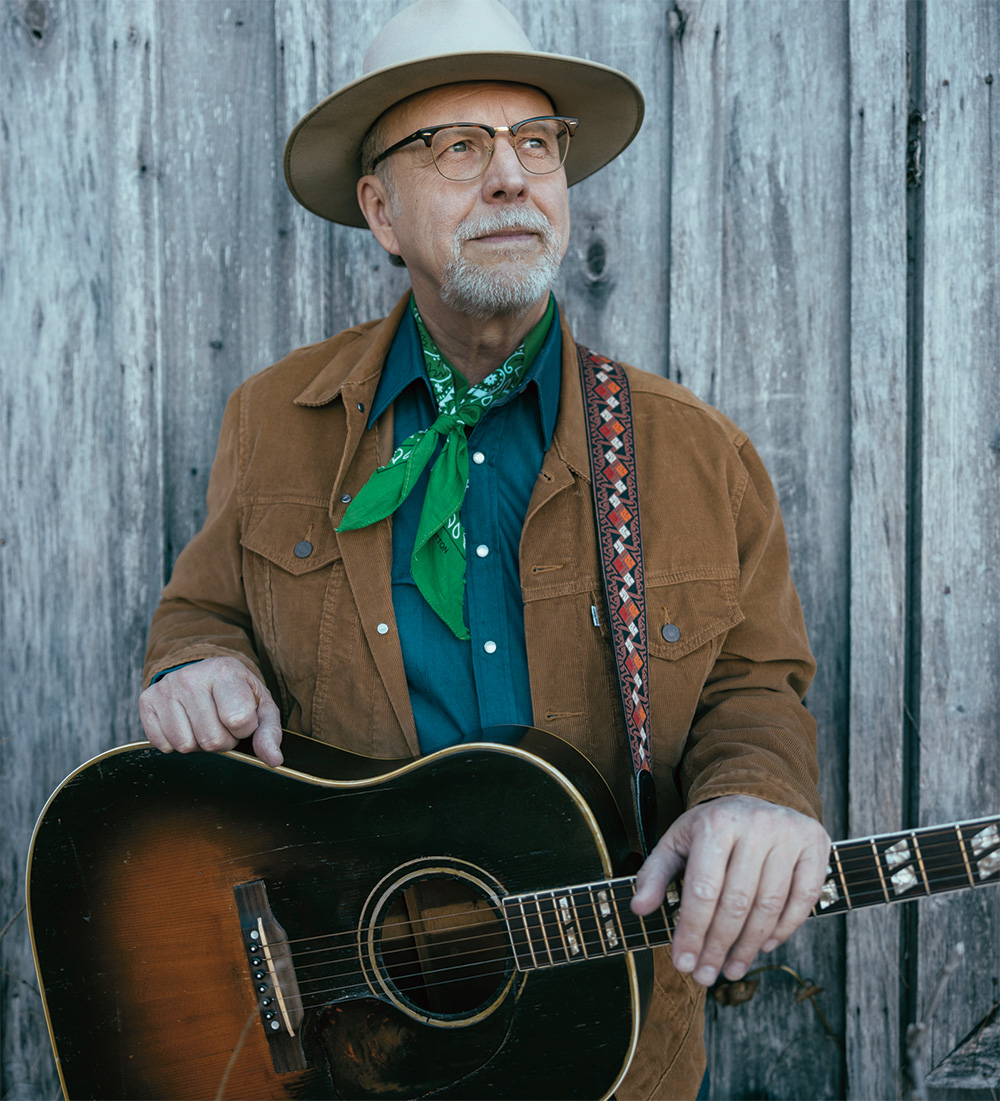

Sonic chameleon that he is, a guy like Webb Wilder doesn’t overthink where his pioneering Americana sound comes from. To him, the source is obvious: It’s Mississippi.

“Mississippi is Afro-Celtic,” he says, an economical way of explaining the depth of African American rhythm and Scots-Irish melody that runs through the music of his home state and through his own, from the garage bands of his Hattiesburg youth to the stages and recording studios he haunts today.

Five decades into his roots-rock career, that same blend powers Hillbilly Speedball, Wilder’s first album in five years. Moving seamlessly among country, rock, blues, and British Invasion pop styles, and with guests like Vince Gill, David Grissom, Richard Bennett, and Fats Kaplan joining the fun, Wilder is still reaping rewards from the Americana soil he helped till in the first place. For an artist who’s never fit neatly anywhere, it sounds perfectly at home.

Born John Webb McMurry in 1954, Wilder grew up surrounded by family members who had seen the birth of modern American music up close. His uncle and aunt, Willard and Lillian McMurry, founded Trumpet Records in Jackson in 1951, releasing iconic blues records, including Elmore James’s Dust My Broom, as well as music by Sonny Boy Williamson II and other early blues artists.

“I thought all my relatives were lovable squares,” he says. “Turns out, some of them were super hip.”

Wilder’s gift for music predates his gift for gab (more on that in a bit). As one of his aunts told him, he sang long before he ever spoke. And by age twelve, he had his first guitar.

Hattiesburg wasn’t known for its music scene, but kids everywhere were learning how to make noise. “From age fourteen on, I was in a band,” he says. “We had guitars, amps, maybe a fuzz pedal. We just did it.” His education came from the radio and record bins, where he soaked up tunes by Hank Williams, Merle Haggard, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones.

As he learned more about Trumpet Records, the scale of what had been happening just up the road started to sink in. Songs by Jimmy Swan, released years before he veered off course and ran for governor as a segregationist, hewed closer to country music. “If you hear the old Jimmy Swan records, he sounds a lot like Hank Williams,” Wilder says. That connection between country and blues, or between the honky-tonks and the juke joints, gave Wilder a foundation for everything that would come later. “She [Lillian McMurry] encouraged me and told me lots of stories and tried to connect me with people,” he says.

One of those connections led to songwriter Dan Tyler, who became part of the same Nashville orbit Wilder would later join. But before that, he spent time finding his sound in other places. He first came to Nashville in 1974, around the time he bought Gram Parsons’s Grievous Angel and fell in love with what people were calling progressive country. That music pointed him toward Austin, where he moved with his band Everready in January 1976.

By the 1980s, Wilder had returned to Nashville, where his mix of rock, blues, and country didn’t fit neatly into any label category. But it didn’t have to. His approach was simple—play what felt true and keep humor close at hand. “If you grew up in Mississippi, if it doesn’t influence you, you have no soul,” he says. He called his band the Beatnecks and in 1986 released his debut, It Came from Nashville, a cult favorite that set his tone for good as part Southern gothic, part barroom rave-up.

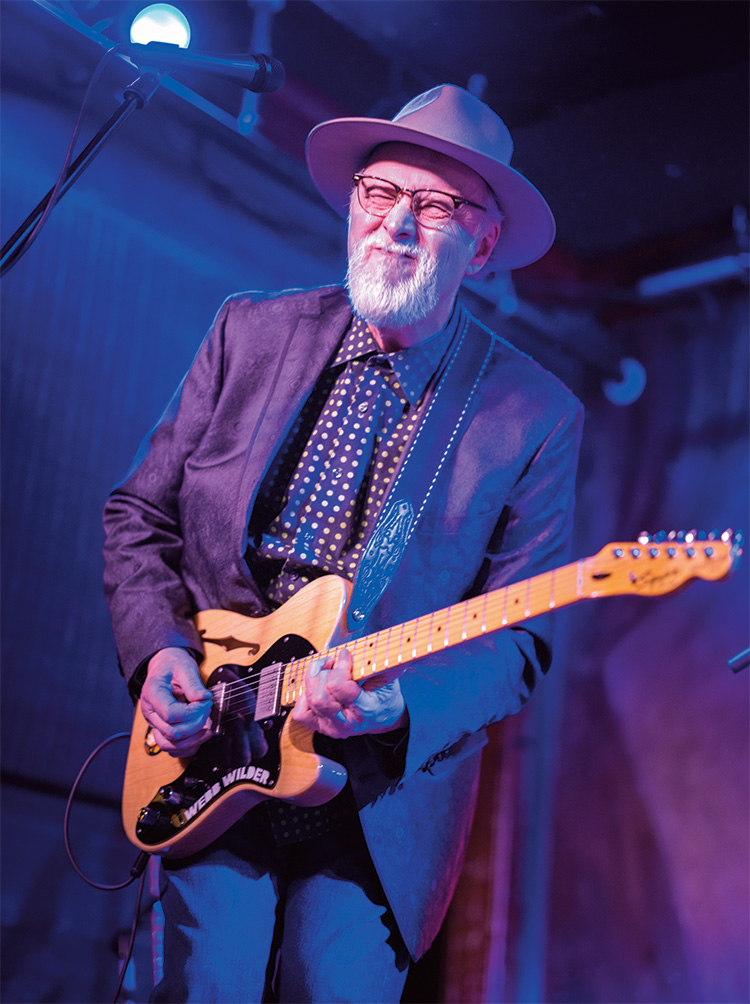

Wilder’s music career carried him through major-label album releases, MTV airplay, and tours across the U.S. and Europe. “I’m proud of the records, I’m proud of 90 percent of the performances,” he says, adding that he’s realistic about where his brand of off-kilter rock and roll places him in the music world. “I was probably too quirky for stardom,” he says, “but I’ve had a career without having hits.”

Fortunately, Hollywood talent scouts knew a good character when they saw him. After bringing his roots-rockabilly persona to life in short films like Webb Wilder, Private Eye in the 1980s, he eventually made his way to the big screen. Wilder landed the role of Ned in director Peter Bogdanovich’s 1993 movie The Thing Called Love, helping bring realism to the story of a fictional aspiring country star in Nashville. The movie starred Samantha Mathis, River Phoenix, and Sandra Bullock, and was one of Phoenix’s final projects before his untimely death that October.

When he’s not riling up crowds from onstage or working on new music, Wilder now puts his pipes to good use on the radio. He was one of the first DJs hired by XM Satellite Radio when it launched in 2001, and he now hosts a regular show five days a week on WMOT-FM, Nashville’s NPR affiliate that produces plenty of roots-oriented original content. He laughs about the workload, but the joy in his voice is plain. “I love playing records and talking about the music.”

Downtime during the COVID pandemic, when touring and live gigs slowed, allowed him to turn his focus back to recording. The sessions took off after guitarist David Grissom sent him a song that would become the title track of his new album. “He said, ‘I’ve written a new song. I want to get your opinion on it,’ Wilder says. ‘[The song] “Hillbilly Speedball” is a good, dumb hook, but it’s a substantive song about a serious subject.” Throughout his thirteenth album, the songs stretch across his influences, from country to blues to rock, with the ease of someone who’s been crossing those lines his whole life.

At 70, the Mississippi Musicians Hall of Fame inductee’s voice still carries the grain of a storyteller who’s lived every mile of it. He’s seen musical fashions come and go, watched Americana evolve from an idea into an industry, and stayed rooted in what first moved him. His story runs parallel to the music he plays—Southern-born, road-tested, and never far in spirit or sound from the music of the Mississippi Delta.

As Wilder continues to create music and uplift the roots music scene from his microphone, no matter where it’s placed, he knows the work itself has always been his true reward.

“I never got the big break,” he says. “But I’ve had a life in music. And that’s all I ever wanted.”