By Katie Tims • Photography by Rory Doyle

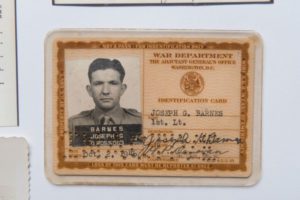

Joe Barnes was a farmer’s kid from the Mississippi Delta. He wanted to teach children, build a family, and make a decent wage on the outskirts of the Great Depression. But World War II intervened. Barnes shipped off to basic training and joined the 36th Combat Infantry. He fought deadly battles in Italy, earned the Bronze Star and Purple Heart, received a battlefield commission, took a sniper’s bullet in France, and then found true love in Battle Creek, Michigan.

Joe Barns is an American hero.

On a Dirt Road

Barnes was born in Leake County, Mississippi, a rural area northeast of Jackson. It was 1919 and Highway 25, now a four-lane highway, was still a dirt road. Times were tough and the people tougher. On 120 acres near Carthage, Press Barnes grew cotton and raised cattle. His wife, Myrtle, ran the household and kept track of their three sons: Barnes and his younger brothers, Bernell and Norman.

Barnes was born in Leake County, Mississippi, a rural area northeast of Jackson. It was 1919 and Highway 25, now a four-lane highway, was still a dirt road. Times were tough and the people tougher. On 120 acres near Carthage, Press Barnes grew cotton and raised cattle. His wife, Myrtle, ran the household and kept track of their three sons: Barnes and his younger brothers, Bernell and Norman.

“It was a hard life,” recalls Barnes about his upbringing. “Mom cooked on a wood stove, and we didn’t have electricity until I was a little older.”

Barnes was barely seven when he started working alongside his father. The milked a dozen cows before breakfast, and they plowed the fields with a mule, one row at a time. Long days for a little guy.

“That’s the way it was. Back in those days, about twenty acres was all you could grow because you had to do everything by hand,” Barnes says. “My dad had two sharecroppers, and all of us kids picked cotton.”

At the time, Merrydale School in Leake County served all grades. Its 1937 senior class had three students—two girls and Barnes.

“I always said I was the smartest boy!” he quips with a laugh. “Six started our senior year, and three dropped out for one reason or another. It was harder to stay in school in those days because everyone was so poor.”

The Great Depression raged, and few Leake County students made it to college. There was barely money to survive, let alone fund an advanced education. But Barnes was determined. In 1937 he started at East Central Community College in Decatur, Mississippi, taking general studies with the goal of becoming a teacher. He and three friends lived in a little two-room house and supported themselves by working on a local farm for ten cents an hour.

In 1939, he got his first job teaching at an elementary school in Kosciusko, making $57.50 per month. He took summer classes at Mississippi State University and then went back to teaching the next year, making $2 more per month. He was educated, making a decent wage on his way.

But sometimes a man’s way doesn’t go as expected.

GoArmy!

In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and World War II began. America’s military machine revved to life, and Barnes registered for the draft. In May 1941 he left for basic training at Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg and then transferred to Camp Wolters in Mineral Wells, Texas. He joined the 36th Infantry Division, which trained for over a year and then shipped out in April 1943.

“We were awfully crowded,” Barnes recalls about that fourteen-day journey from New York City to Oran, Africa. “We were stacked up four or five deep in a room with bunk beds. They fed us just enough to survive.”

In Africa, the 36th Infantry Division—also known as the “Fighting 36th”—trained and performed maneuvers. Assignments were made.

“Every battalion had three rifle platoons and one weapons platoon. I was in a weapons platoon,” says Barnes. “My platoon had two machine guns and three mortar squads. I started off as a gunner in the mortar squad.”

(No) Simple Landing

On September 5, 1943, the 36th Infantry Division shipped out. They were headed to Italy—the first Americans to enter combat on the European continent.

“On the boat the afternoon before we were supposed to land near Salerno, Italy, they called all of us together. They told us that Italy had surrendered. They didn’t think landing would be too much of a job,” Barnes recalls.

As a result, fewer preemptive measures were taken to soften the enemy’s coastal line. No shelling. No bombing. Early the next morning when Barnes and his three squads—two machine guns and one mortar—made what was supposed to be a “simple” landing. They were dumped into waist-deep ocean water near Paestum (a town about thirty miles south of Salerno), about one hundred yards from shore.

But there had been a mix-up. According to Barnes, he and his men were sent to the wrong beach at the wrong time.

And the Germans were waiting. They could not see the Americans, but they could hear water sloshing and the soldiers coming. Gunfire sprayed the beach and into the pre-dawn darkness. Barnes and his men ran ashore and ducked behind the sand dunes. The firing continued.

“There wasn’t another soul around,” he recalls. “There we were—twenty men trying to invade Italy all by ourselves.”

From his vantage point, the Germans were firing guns from behind a clump of bushes.

“I told my boys, ‘Let’s set up that mortar and knock out that machine gun nest,’” Barnes recalls. “But before we fired, that clump of bushes started moving off. It was actually a tank camouflaged as bushes!”

Had the Germans spotted the Americans’ location, Barnes and the other soldiers probably would not have made it. Instead, the firing stopped, and the tank rumbled off in the opposite direction.

“I told my platoon, ‘Just fold that little mortar up and stay quiet as we can.’ Those next ten or fifteen minutes seemed like eternity.”

At last, the other American troops landed, and the shelling began. Barnes’s platoon rejoined its battalion a few days later.

“Our outfit was surprised to see us,” hes says. “They thought we’d all been killed. Somebody had reported that he’d ‘seen Sergeant Barnes laying on the beach, dead.’ Well, that was not true, thankfully.”

Tough Beyond Measure

Italy may have surrendered, but the Germans didn’t agree. They fought hard, and the results were deadly. Many men were killed in this “simple” landing. Once the Americans gained a foothold at Salerno and the fighting paused, Barnes’s platoon was ordered to retrieve dead soldiers along the beach.

“They had us pick up people who were not in our outfit to make it not quite as bad,” he says. “Every solider had a mattress cover, and we used those as caskets, which was hard because it was hot, and the bodies had been there for a week. It was terrible.” (In total, the 36th Infantry Division suffered 19,466 battle casualties—the third highest among the divisions that fought in the European Theater.)

During the winter months of 1943-44, Barnes and his fellow troops battled their way through the enemy-infested Italian mountains. The going was so rough, rocky, and steep that supplies, ammunition, and water had to be transported by men lugging heavily loaded backpacks. The going was painful, wet, muddy, and ungodly cold.

“We didn’t have the right clothes to keep us dry,” recalls Barnes. “We nearly froze. We had a lot of casualties due to the weather. It was real tough.”

The fight went from one mountaintop to the next, never letting up. One night, Barnes and his platoon leader, a lieutenant, hunkered in one foxhole as a constant barrage of shellfire blasted overhead. The platoon’s gunner and assistant gunner hid in another a few yards away. Suddenly, a shell screamed across the black sky and straight down that gunner’s foxhole.

“I jumped out and ran to see if I could help,” Barnes says about his immediate reaction.

Was there a moment’s hesitation?

“No,” Barnes answers plainly. “I heard them scream and thought they needed me. Of course, they didn’t—they were blown all to pieces. Those were two real good men we lost. We had a lot of good men killed.”

Barnes received the Bronze Star medal for his courageous action.

Officer Joe Barnes

“The officers that came to us right out of school didn’t last long—they got killed or wounded,” says Barnes. “They hadn’t seen a day of combat, and they didn’t know what to do. So even though I was platoon sergeant, I did the job of the platoon leader. I led the platoon—thirty or forty men—through a lot of combat in Italy. They all respected me.”

The company commander said he’d rather have an experienced solider than one more educated lieutenant. He offered the promotion to Barnes, who promptly turned it down.

“I thanked him and said I wanted to stay right where I was,” he recalls.

Barnes believed a promotion would change the dynamic between him and his men.

“Officers and enlisted men don’t associate with each other,” he explains. “Officers have to be saluted by the enlisted men and served—it’s all business. My men and I had been through a lot together, and I wanted to stay with them.”

The commander insisted, however. He promised Barnes that he could continue with the same platoon. A few days later, the US Army discharged Joe Barnes the enlisted soldier and then re-enlisted Second Lieutenant Joe Barnes.

Circuitous Route Home

The Fighting 36th advanced through northern Italy and into France, wiping out German strongholds along the way. The going was especially bad in one heavily wooded area near the Moselle River in the Vosges Mountains.

“We were trying to take an area, and the Germans had snipers in the trees picking off our soldiers,” Barnes recalls. “The only opening was a little road.”

The only way to advance was to shoot mortar shells ahead, which created a sniper-free tree tunnel through which the Americans progressed. However, the weapon had to be positioned in the open, far from tree branches and undergrowth. It was there, in the middle of that little dirt road, that a sniper’s bullet ripped through Barnes’s right leg. He was rescued and transported to a field hospital. From there, he went to a bigger hospital in Italy, where he stayed for a couple of weeks.

One day, an orderly came by to ask Barnes some questions. “How much do you weigh? How much luggage do you have?”

“What’s this all about?” Barnes asked.

“Well, sir, you’re fixin’ to go home,” the orderly answered.

Barnes was ecstatic. He remembers, “I couldn’t eat another bite—I was so excited!”

Happenstance

It was October 1944, and Barnes was home—well, almost. The bullet severed a sensory nerve in his leg, which required multiple surgeries and advanced care. Barnes stayed for months at health care facilities in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and Battle Creek, Michigan. It was at the latter that Barnes formed a life-long friendship with fellow World War II veteran, United States Senator, and vice presidential candidate Bob Dole.

“That was a good back rub!” Barnes remembers with a laugh.

Following that surgery, Barnes asked Dottie for a date. They were married five weeks later—one day before her transfer to England. Dottie’s father, a Methodist minister, conducted the wedding ceremony in the family’s living room in Peoria, Illinois.

Home is Mississippi

World War II ended, and Barnes’s leg healed. He and Dottie moved to Mississippi, and Barnes finished his studies at MSU. The couple moved to Kilmichael, and they had two girls, Linda and Julie. Barnes worked first as an ag teacher and then took a job managing a farm owned by the Purina company. In 1962, Barnes returned to academics and took an ag teacher job in Rosedale. He eventually became the school district’s superintendent. As for Dottie, she worked the whole time as secretary in the superintendent’s office.

They both retired in 1982.

“After that, we took a walk every day,” he says. “We would talk a lot about how lucky we were.”

And they were—for a little while. Shortly thereafter, Dottie was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, and she passed sixteen months later. They were married for forty-two years.

Eventually, Barnes found love again with fellow Rosedale resident Gladys Welshans, whose husband had also succumbed to cancer. Today, at one hundred and eighty-five, the two are still going strong. Next year will be their thirtieth anniversary.

“It’s been a good life,” Barnes says, in reference to his one hundredth birthday last July. “I’ve seen a lot. I’ve done a lot. I have family, friends, and so much to be thankful for.”

6 thoughts on “A Hero Turns 100 – The Amazing Life of Joe Barnes”

What a wonderful story arising out of WWII and I really enjoyed the article . Et

God Bless You, sir, and thank you for your service to our country!

I am so thankful for the wonderful life of service that Joe Barnes has lived. Thank you, Joe, for your gift of service to our country.

What an inspiring story. I love to hear our World War II veteran’s tell their story. They have so much love and dedication for our country. Thank you Delta Magazine for interviewing this incredible man.

Wow! What an amazing story of heroism and survival. Thank you, Joe, for your service!

Thank God for soldiers like this!