By JIM BEAUGEZ

The Black Keys return to their roots with Delta Kream, a tribute to their Mississippi Delta and Hill Country heroes

Not long after his marathon thirteen-hour drive from Akron, Ohio, ended in Greenville, Mississippi, in the late 1990s, Dan Auerbach ran out of a downtown café without even touching the plate of crawfish placed in front of him just moments earlier.

It was no fault of the cuisine, though. No matter how good those mudbugs may have been, Auerbach didn’t come all that way to pinch a few redtails. It happened that at the same moment, the man he did come to find—Delta bluesman T-Model Ford—had just arrived.

“He pulled up in a Lincoln, and he was pulling his plywood trailer that had ‘T-Model Ford, The Taildragger’ hand painted on it,” remembers Auerbach, frontman and guitarist of Grammy-winning, bluesy rock duo The Black Keys. “The back of that trailer is what we saw the rest of our time there. We were just following that trailer all over.”

Auerbach had come under the spell of the Mississippi blues music created by Ford (James Lewis Carter Ford by birth), Junior Kimbrough, and R.L. Burnside and released by Oxford’s Fat Possum Records in the 1990s. The previous year, he and his father had traveled to the northern Mississippi Hill Country to chase that regional strain of blues to its home turf, Kimbrough’s juke joint in Chulahoma. It was no big deal, then, for Auerbach to recruit a buddy, throw a couple of sleeping bags in the back, and hit the road on a new adventure to the Mississippi Delta.

Plus, he didn’t think he was coming in cold with Ford. Auerbach had met him at the Cleveland, Ohio, stop of the Juke Joint Caravan tour organized by Fat Possum, which released his first five records beginning with Pee-Wee Get My Gun in 1997. It likely wasn’t a robust memory that accounted for Ford’s interest in the enthusiastic young man with the guitar in his car, though. “He said he [remembered me], but I don’t think he did. But he told me he was playing, so we said ‘great,’ that we’d follow him.”

Auerbach followed Ford and his trailer from paved city streets to dirt and gravel roads, around oxbows and over levees to his first gig of the day, a house party and barbecue at a double-wide trailer in the middle of a field. Despite being a party-crashing out-of-towner, he found the hosts friendly; they welcomed him to their table and fed him, and he spent the afternoon plugged into the same Peavey amplifier as Ford, playing along.

“I’d been obsessing over his records, so I think he realized I knew all his stuff and he was really pleased, you know what I mean?” Auerbach says. “It was great, but at the same time, he was also trying to mess with me and trying to throw me off—making the changes crazy. And he was smiling about it. But he was just having a little fun.”

The same pattern repeated later that night, with Auerbach following Ford to a cinderblock building in another remote field and sitting in on another set. Afterward, he took up Ford’s invitation to crash on the floor in a spare room at his home. By the next time Auerbach made it to Mississippi, he and childhood friend Patrick Carney had channeled their love of Mississippi Delta and Hill Country blues into The Black Keys and were signing their own record deal with Fat Possum.

“The history of the Delta and the music that’s come from it,” Carney begins, before pausing to collect his thoughts—”I always feel like, when you roll into Memphis, all the way down to New Orleans, that whole stretch feels very touched, very special, and I can’t put my finger on it. Like there’s a different energy there.”

Nine albums into a career that had taken them around the world more than once, earned five Grammy Awards, and notched four Gold or Platinum records, that’s exactly where The Black Keys ended up. Not even a week removed from their 2019 tour in support of Let’s Rock [Easy Eye Sound/Nonesuch], Auerbach caught inspiration while jamming with guitarist Kenny Brown and bassist Eric Deaton on sessions for Robert Finley. It felt so good that he asked them to stay another day and called Carney down to the studio.

The next day, the songs of the Delta and Hill Country poured out of them. As soon as one song was done, someone called out the next tune. They dove deep into the Burnside and Kimbrough catalogs—the specialties of their guests, Brown and Deaton, who had played extensively with the Hill Country legends—as well as Tutwiler native John Lee Hooker and Ranie Burnette, who was from the Pleasant Grove community in western Panola County.

Auerbach let the tape run, and the collaboration came together as Delta Kream [Easy Eye Sound/Nonesuch], an eleven-song love letter to Mississippi music and the people who created it. “Just listening to those guys play was really exciting, to get to gel with some new energy in the studio,” says Carney. “Eric’s bass was really the glue holding everything together, and Kenny’s guitar is just like electricity.”

Although in the past they had tracked live and collaborated with artists like Danger Mouse and the one-off Blakroc with Damon Dash and Mos Def, Delta Kream marks the first time The Black Keys have ever recorded bass, rhythm and lead guitars, drums, and vocals at the same time. The whole affair has a juke joint feel, right down to the occasional, between-song banter. But even Carney wasn’t sure how it would turn out.

“For Dan and me to sit and play with those guys was really cool and very exciting, [but] we hadn’t played anything that sounded remotely like that in years,” he says. “To fall back into it without any rehearsal and just cut a whole record in two afternoons was pretty cool.”

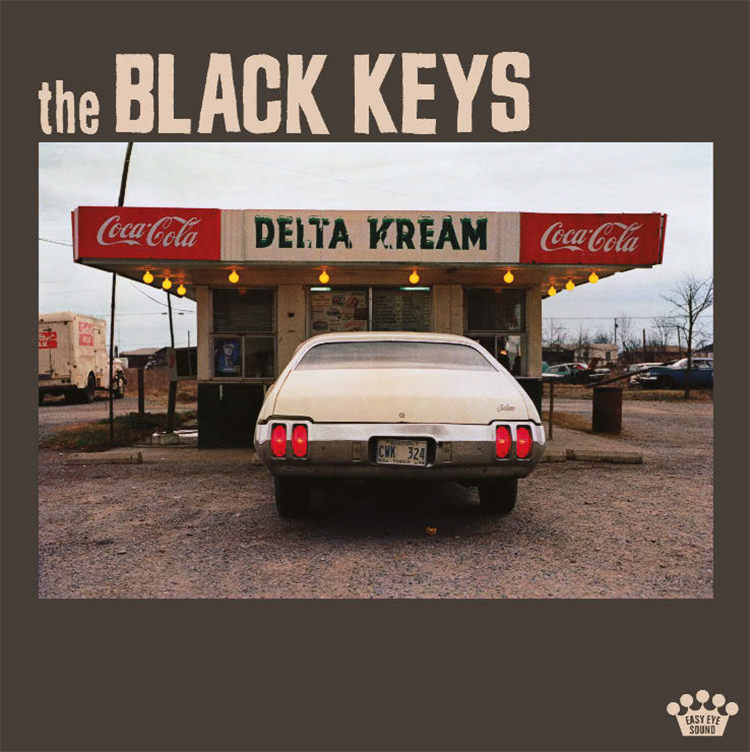

The album is named for a 1970s William Eggleston photograph of the former Delta Kream shop in Tunica, which is also featured on the album cover. Alongside the music, the package feels like a throwback to the days when juke joints weren’t too hard to find. So when it came time to put together a plan for promoting Delta Kream in the middle of a pandemic, the band hit upon the idea of going back to Mississippi.

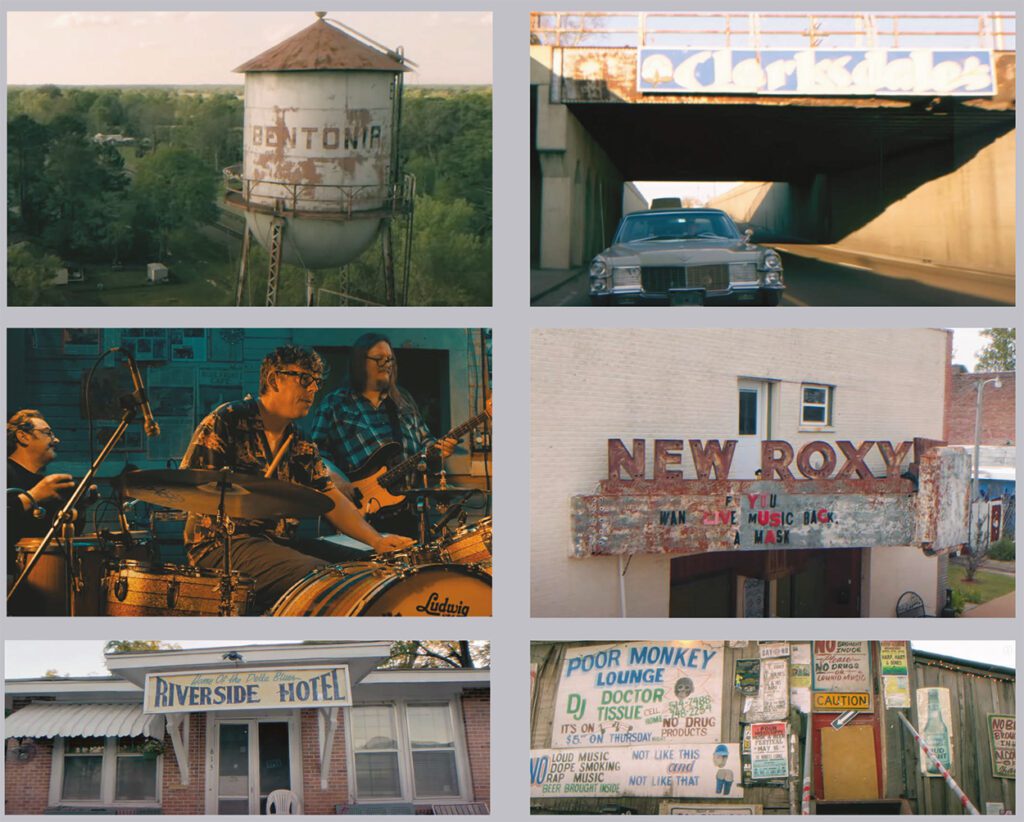

Auerbach, especially, had kept a toe in the muddy Mississippi waters, recording and releasing the posthumous The Angels in Heaven Done Signed My Name by Leo “Bud” Welch in 2019. He also collaborated with Jimmy “Duck” Holmes, the sole living connection to the Bentonia style—a darker, less structured cousin to Delta blues played by Henry Stuckey and Skip James—on the Grammy-nominated Cypress Grove [Easy Eye Sound]. Oddly enough, though, they had never been to Holmes’s Blue Front Café in Bentonia. The seed germinated quickly, and they soon found themselves motoring south from Nashville.

“We’d had a good time making a record with Jimmy, and he played with us out on the road, so we had a good relationship,” says Auerbach. “He had invited us down, so we basically took him up on the offer. It was amazing—oldest [active] juke joint in the world; his parents opened it. It’s really cool. It was the perfect place to play that music, too.”

Despite speaking the musical language fluently, Carney had never actually visited a juke joint until that April trip when he, Auerbach, and the Delta Kream backing band set up at the Blue Front Café to record a promotional concert, which they later parceled out as segments for The Late Show with Stephen Colbert and an exclusive livestream for Spotify. The video for Hooker’s “Crawling King Snake” mixes footage of the same Blue Front performance with various scenes from around the Delta.

“I always wanted to make the trip [to Mississippi],” says Carney, “and it’s weird that we never made the trip together to go to a juke joint or anything until this past spring. And we were talking about what to do, how to promote Delta Kream during a pandemic when we weren’t going to tour on it or anything, and Dan suggested we go to Bentonia. I think we both agreed that we wanted to do something in Mississippi, and he was like, we should go play Jimmy ‘Duck’ Holmes’s Blue Front Café.”

Still, Carney had soaked up plenty of Delta-adjacent experiences while growing up in Akron, Ohio. Mississippi, the Delta and Hill Country regions in particular, serves as a suitable analogue for the northeastern corner of Ohio where Auerbach and Carney grew up. In the open expanses, the winding, forested pockets, and the postcard layouts of small towns huddled around sleepy town squares, they found the comfort of the familiar.

“North Mississippi is very desolate as far as population density, but it definitely reminded me of parts of Ohio,” says Carney. “You could get out of Akron and in about fifteen minutes you can be in pretty rural farming communities.”

One thing northwestern Ohio had that eluded Mississippi, though, was an urban center on the order of Cleveland, just forty miles north of Akron. That’s where Auerbach and Carney saw T-Model Ford, Paul “Wine” Jones, R.L. Burnside, and other Mississippi bluesmen perform at rock ‘n’ roll clubs like the Euclid Tavern. Of course, they might argue Mississippi had plenty of places to hear the blues. Had, that is—because without Junior’s Place in Chulahoma or Po’ Monkey’s in Merigold, there are few remaining places to experience blues in its natural setting.

The night of their performance in Bentonia, word eventually spread over social media that The Black Keys were in town. But the fans who showed up weren’t just there for Auerbach and Carney. After COVID restrictions had damped festivities for more than a year, people showed up and joined in celebration. The Blue Front Café, the oldest continually operating outpost of the blues, was officially back.

“[The history] is all around you there,” says Auerbach. “You see it in the photos on the walls, the signs on the buildings. It’s amazing, really, to be around. But, also, it’s living and breathing and thriving, and there’s people there.”

As the band pulled away from the Blue Front Café that night, the juke joint was still packed with people. Holmes was playing music on the front porch with a group of young fans who had shown up from out of town, maybe hoping some of the Delta mojo would rub off on them. Or maybe they had just traveled a long way for a chance to meet their hero.