Written and photographed by KAREN PULFER FOCHT

A musical journey well-travelled

He sings about being in love with big, fat women, being henpecked and broken-hearted, about cheating women, chicken heads, and porcupine meat. Entertainer and at age eighty-eight, Mississippi bluesman Bobby Rush will say or do just about anything to make his audience laugh.

Rush isn’t just a bluesman—he’s a comedian and the ultimate showman.

“I take a chance and do things other guys wouldn’t dare to do,” Rush recently said about his sometimes-racy performances. He recalls as a young child, being a clown, he learned quickly, “I had a gift that could get me through the door. I’m a comedian.”

However, getting through the door wasn’t always something to laugh about. It didn’t mean he was always treated right.

He tells stories of playing music for cheeseburgers on the Chitlin Circuit and having to play behind a curtain because the white audience that came to hear his music didn’t want to see his black face. “I didn’t want anyone to know I was hurting. I found a way to make that funny; I was funny from behind the curtain. I dealt with it through humor. I’d laugh about myself and about the garbage man stealing my wife.”

His music is his escape.

At eighty-three, he was honored with a long-overdue Grammy. He looks like he’s in his fifties. He is tall, thin, and energetic. He has smooth skin and an even smoother voice. He is a consummate entertainer.

Rush was once called “King of the Chitlin Circuit,” a title he didn’t like and would have never given himself. He has felt disrespected many times in his lifetime.

However, he pushed forward with over 350 recordings and a career where he plays over two hundred dates per year. He says that he has been blessed. “Music gave me some opportunities that I never would have had as a Black man; I would never have gotten through those doors. Emmett Ellis Jr. (his given name) would never have gotten through those doors.”

When things are tough, he says he grabs his guitar and writes songs. “You write what you know about,” and Rush knows the blues. Songs come to him often at odd times; “I will write on toilet paper if I have to.”

He grew up in a household filled with plenty of love and spiritual grounding.

“When I was a child, we were poor and we had no money, but we had love. Love is a healer of all things.” His father, a preacher, was his mentor. “He was a kind man, and he was everything to me.”

His mother was blond and blue-eyed. She was the granddaughter of a powerful white landowner in the area. In the segregated South, he said when the family was in public, she was referred to as his “babysitter.”

As he learned about prejudice in the South, like many, he decided to venture north where he believed things were better. In Chicago, he met many of the great bluesmen who also chose to migrate north. Legends like Howlin’ Wolf, Albert King, Muddy Waters, and Little Walter. He did what he had to do to learn his craft. When times were lean, Rush sold hot dogs to help make ends meet.

Before leaving home at age fourteen, a good attitude and work ethic was instilled in him. Whether Rush was chopping cotton, carrying water, pumping gas, or later in life, writing songs, he says he has always tried to do his very best.

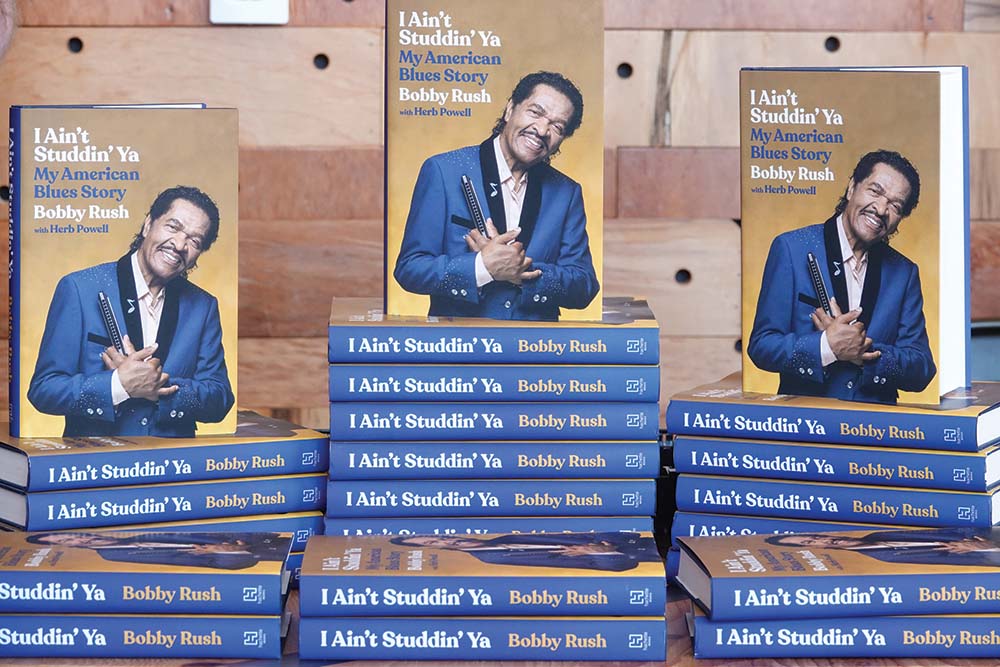

While he thinks it is important to write about the valleys and hardships in his new book I Ain’t Studdin’ Ya, he also wants to be an inspiration to others. He remains funny and upbeat. “I don’t have a chip on my shoulder about nothing or no one.”

When Rush looks back on his life, he says he is thankful for what his life is. “When I think about what it could have been, I am so blessed. All along the way, I have asked God to lead me and teach me to do the right thing so that I make the right decision.”

He never drank or used drugs. “There are some things I wish I hadn’t done, but if I had it to do over, I would change very little.”

He played blues in the Arkansas Delta before spending decades living in Chicago. He returned to the South in the early eighties, and when he is not touring, he comes home to a wife and family in Mississippi where he likes to go to church, fish, and spend quiet time alone. He believes Mississippi has always been underrated and has been unjustly given a bad name.

Throughout his lifetime, Rush has been disappointed to learn that racial problems exist all over the world and not just in the South. It was in the north, in Illinois, that he had to play behind the curtain. He realized that there was no escaping racism, even after his pilgrimage north. That gave him the blues.

As for the future of the blues? The late B.B. King talked about how so many of the great bluesmen came from Mississippi. Rush also feels that it is very important for people to know the history of blues music and where it came from. Rush is one of the last elder bluesmen standing, and he says that it scares him to death. He is passionate about encouraging younger people to continue the tradition of blues music. “Black kids don’t want to be part of the blues; they don’t identify with the origins of the blues.”

Many white artists are now carrying the music forward. Rush is thankful for that. However, he wants people to know where the blues came from, that it came from the black community. Blues was born out of pain and in the cotton fields and the segregated South.

He is thankful for his longevity after watching many of his colleagues lowered into the ground.

While pulling on your heartstrings, he looks you in the eye and tells you that he has a problem; he pulls out his harmonica, lays down a blues lick, and continues, “I’ve got a problem with my woman, with my girlfriend and my wife. I love number one, and I love number two, but number three does things number one and number two won’t do.”

Far from the days he was selling albums from the trunk of his car, he is now enjoying the notoriety that is finding him at every turn. On a recent trip to Memphis, he couldn’t walk down the street without being stopped by people that drove by, including a trolley driver. Rush is recognized nationally and internationally. He once played to Black-only audiences on the Chitlin Circuit. Now, he’s built a national and international fan base that draws a diverse audience. He plays at auditoriums, wineries, and performing arts centers.

He remembers the days when they wouldn’t hire a Black man who sounded like himself, but they would hire a white man who sounded Black.

Now, white guys and younger guys want to record with him. “Now they see me as Bobby Rush, the bluesman, and they love me,” he says proudly.

Rush has been working with music students at Rhodes College in Memphis where he was given an honorary degree this spring. He is now Dr. Rush.

For Rush, one of the most meaningful things about being so highly acclaimed late in life, is that it allows him to help others. He says he can now contribute to his family and friends in ways he was never able to do before. “I can do things now for people that can’t do for themselves and for people who need it more than me.”

As a two-time Grammy award winner, the “International Dean of the Blues” from Mississippi doesn’t have to work for cheeseburgers anymore.

“I’m a blues-man, I’m a blues-man

Ah, that’s all I know

I sing the blues y’all, everywhere I go.

at the historic Levitt Shell, a popular outdoor

venue in Memphis, Summer of 2021.