By JIM BEAUGEZ • Photography by GREG CAMPBELL

Lynyrd Skynyrd was one of the biggest rock ‘n’ roll bands in America. Then the unthinkable happened.

Southern rock ‘n’ rollers Lynyrd Skynyrd, whose iconic songs “Sweet Home Alabama” and “Free Bird” have become cross-generational anthems, were riding high in October 1977. The addition of Steve Gaines to their three-guitar army had energized the band as they shook off the hangover of Labor Day 1976, the day co-guitarists Allen Collins and Gary Rossington wrecked their cars in separate incidents while impaired by booze and pills.

With Street Survivors, the band’s fifth studio album, frontman and mastermind Ronnie Van Zant aimed to turn things around, and he didn’t mince words. The title itself is a nod to their rough, brawling past—which Van Zant hoped was behind them—while the lyrics to “That Smell” redressed Collins and Rossington for their reckless behavior that derailed a lucrative tour.

On October 27, just ten days after the release of Street Survivors, the album was certified gold. In December, it was awarded platinum certification for shipments of one million copies and hit number five on the Billboard Top 200 albums chart—the band’s fastest-selling album yet. But by then, there wasn’t a band left to celebrate.

While en route from Greenville, South Carolina, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, at 6:42 p.m. on October 20, the Convair CV-240 jet the band had leased lost power to its right engine. The left engine died soon after, and the twenty-four passengers, pilot, and co-pilot spent the next four minutes gliding as the aircraft steadily lost elevation, clipping the tree line for five hundred feet before ripping apart as it crashed four miles northwest of Gillsburg, Mississippi.

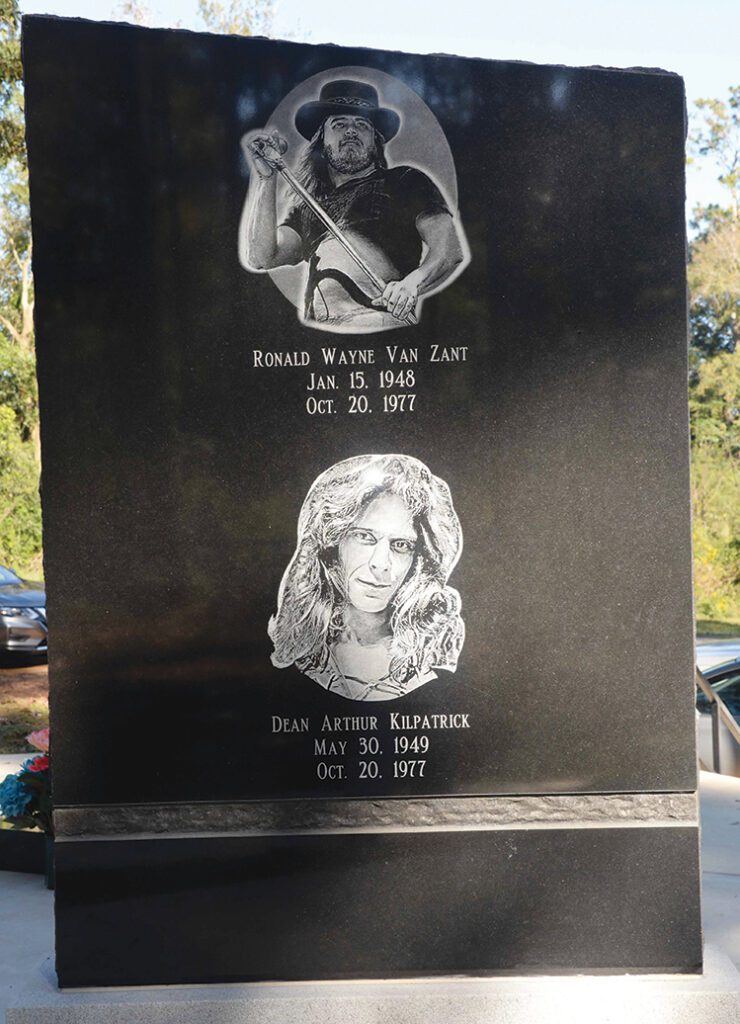

Forty-three years and a day later, Dwain Easley sits in a pickup on a plot of land he donated for the Lynyrd Skynyrd Monument, a series of three granite markers commemorating the band, the first responders, and the six people who died that day—Ronnie Van Zant, Steve Gaines, backup singer Cassie Gaines, assistant tour manager Dean Kilpatrick, pilot Walter McCreary, and co-pilot William Gray.

Through a nearby gate and down a winding path, he pulls up to an open-air workshop where artifacts recovered from the crash site are laid out on a long table: mangled sheet metal and swatches of beige shag carpet, bent and frayed wires affixed to pieces of metal gadgetry, a completely intact emergency door. Then he sits down in a lawn chair to recount what happened next that autumn evening.

Easley spent the afternoon of October 20, 1977, bow hunting for deer on family land that today surrounds the monument until the eighty-degree heat drove him back home before dusk. He was pouring a cup of coffee when he heard a helicopter flying lower than he thought it should. The phone rang, and his mother answered; there had been a plane crash somewhere in the woods behind their home. Easley and friend Wayne Blades stopped what they were doing and headed out in the fading light to search for the wreckage.

“I went down to talk to some of the guys hauling hay and asked them did they hear anything,” Easley remembered, “and one guy who was all the way in the back said, ‘Yeah I heard something, sounded like train coupling.’ I said, ‘That wasn’t no train’”—it was actually treetops hitting the bottom of the plane’s fuselage during the final moments of the crash.

When the U.S. Coast Guard helicopter, dispatched from a nearby training mission, fixed its searchlight on a location over the trees, Easley knew where to go. He and Blades tore across a quarter-mile of pastures and wooded bottomland to find the fuselage ripped in two and the passengers moaning in pain and screaming for help. Easley climbed into the wreckage and began removing passengers both alive and deceased; by then more responders were on scene to help move them safely away. They worked late into the night alongside emergency crews to move the survivors to a nearby field for staging, then to Southwest Mississippi Regional Medical Center in McComb for treatment.

Lighting technician and rigger Mark Howard was seated on the right side of the plane facing the back, watching the trees get closer and closer, when drummer Artimus Pyle yelled for everyone to buckle up. The crash knocked him unconscious, but he woke briefly when first responder Jamie Wall pulled him from the wreckage, then passed out again. He woke up four days later at University Medical Center in Jackson with a broken collar bone and skull fractures. “I think the first thing I saw was the brother of the road manager,” he says. “I remember asking him who lived. I was in and out for a while.”

After regaining his faculties, Howard got a pass to go down to McComb to retrieve his luggage but declined a visit to the crash site. “I couldn’t do it,” he says. “I just said, ‘Nah, take me back to Jackson; I can’t be here anymore.’ It was pretty freaky.”

Bolivar Medical Center surgeon Dr. Bennie Wright of Cleveland, who was on trauma surgery rotation during the final year of his student residency at the time of the crash, served on the team that treated Howard and the other severely injured survivors at University Medical Center in Jackson. Although he knew the patients were members of the Lynyrd Skynyrd band and crew, he kept his involvement with their care professional. “In addition to hurting and being in pain and trying to recover, they had to deal with the fact that they knew they’d lost some friends,” he says. “I didn’t want to get personal with them.”

Back at home in Texas, Howard’s fight continued—he would eventually have seventeen hip replacements. Doctors readmitted him to a hospital before Christmas 1977 when he had retained enough fluid to gain sixty pounds. He recovered and signed on to work the Willie Nelson tour after his release in January, but he had to confront his trauma again.

“We blew a head gasket in Slidell [Louisiana] on the way to Florida, and they said, ‘We’re gonna have to rent a plane,’” he says. “So we go to the airport, and the exact same type of plane we had just gotten in a crash on two months ago, they wanted us to get on with the equipment and fly to Florida. It was either get on the plane or go home.”

Leland native Paul Abraham, who later served as the band’s tour manager after Lynyrd Skynyrd regrouped with Van Zant’s brother Johnny on vocals in 1987, had become friends with Van Zant and other members after booking them to play the Bolivar County Expo Center in Cleveland on March 7, 1974. The band stuck around the day after the concert, and Abraham showed them around the Delta, visited with bluesman Son Thomas, and hung out at the Greenville bar One Block East. When he heard about the crash over the radio, he was devastated.

“That day pretty much changed my life,” Abraham says. “It hurt my heart so bad. It’s just the hardest thing to have to deal with, losing friends.”

When he was able to get a call through to keyboardist Billy Powell two months later, he wasn’t prepared for what he heard. “Billy is the kind of person that no matter how much it hurt him to talk about it, he really went into graphic detail to me about the plane crash. Whether I wanted to hear it or not, I was gonna hear it. He told me about everything [that happened] until it finally settled down and was quiet [during the plane’s descent]. People whimpering and crying. It was horrible.”

Eerily, the cover artwork of Street Survivors showed the band standing amid towering flames. MCA Records quickly issued a new version of the album jacket without the flames, and “What’s Your Name,” which first charted a week and a half after the crash, peaked at number thirteen on Billboard Hot 100 singles chart in March 1978. The band’s entire discography has sold more than twenty-eight million copies just since the SoundScan reporting era began in 1991 and was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2006, cementing their place in music history.

In a wooded area near the monument, just off the pasture where ambulances and pickup trucks carted the injured and deceased away from the crash site, a lone American beech tree stands among oaks that look scrawny by comparison. Known as the “Free Bird” tree, its thick, rigidly perpendicular trunk is scarred all the way around and six feet up with names and messages carved by Lynyrd Skynyrd fans. But while this may be hallowed ground to them, it’s not the actual crash site.

Easley leads us deeper into the woods on a similarly warm autumn afternoon, where the broad canopy has choked out most of the undergrowth and the ground is carpeted with layers of fallen leaves. We cross the same creek that the first responders and emergency personnel waded that night through waist-deep water, only the lack of rain has rendered the seasonal wash nearly dry. We easily step from sandbar to sandbar to the other side.

At first, it looks like any Mississippi hardwood forest. But with a little coaching on the flight path, a gap in the canopy emerges where the plane descended through the trees and came to rest. Four decades later, the forest hasn’t fully recovered. Once the major pieces of the plane were removed from the site, workers simply turned the remaining debris over into small mounds that today are barely discernible rises on the ground. Fan and archivist Mike Rounsaville loosens some dirt with a shovel to reveal small pieces of metal and carpet hidden in the dirt.

Abraham says that when he signed on to run security for Lynyrd Skynyrd’s 1987 reunion tour, and was later made tour manager, he came to expect trouble when the crash anniversary rolled around.

“One particular day in Concord, California, about six o’clock in the morning, I get a phone call from Johnny [Van Zant], who was in the room next to Leon [Wilkeson, bassist]. He said, ‘Paul, Leon’s in his room either trashing it or somebody’s killing him.’ So I run down the stairs and sure enough, Leon had trashed his whole room. I looked out the window and there was about half a dozen people out there roaming around the wreckage [where he threw] the desk and TV. Things like that happened.”

Abraham, who now lives in Cleveland, joined Judy Van Zant, Ronnie’s widow, and hundreds of other people at the dedication for the Lynyrd Skynyrd Monument on the forty-second anniversary of the crash. Despite his earlier reticence, Mark Howard finally decided to come back to Gillsburg, too, after Marc Frank, the band’s drum tech in 1977 and a fellow crash survivor, talked him into going.

“I really don’t know how to describe how it made me feel,” Howard says. “It was like a calm came over me, like somebody lifted a big weight off my shoulders. Meeting the first responders for the first time was probably the biggest part of it. I met Jamie Wall first, and we both had tears in our eyes. With my seventeen hip replacements, I’m in pain every day of my life, [but] going back to the site eased all that; it made it worthwhile. I don’t know if that makes sense to you or not, but it does to me.”

If you go: Driving southbound or northbound on Interstate 55, watch for the brown historical-interest signs at Exit 8. Take the exit and drive west on Highway 568 for 7.5 miles, then turn left onto Easley Road. The monument is 0.33 miles on the right.

1 thought on “Free Birds”

Awesome article:)) Lynyrd Skynyrd was the best!