By SCOTT BARRETTA • Photography by RORY DOYLE

Updated venue will keep bringing the blues for years to come

Indianola’s Club Ebony is one of the few still-active venues from the glory days of the Chitlin’ Circuit, the nickname for the network of African American venues across the country during the segregation era. Following extensive renovations, the 75-year-old club promises to entertain many more generations of blues fans. Owned and operated by the nearby B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center, the club will celebrate its reopening June 1–3 with concerts each night by artists including Mr. Sipp and Tony Coleman, King’s longtime drummer.

The B.B. King Museum opened to the public in 2008, the same year King purchased Club Ebony from longtime owner Mary Shepard and subsequently transferred its ownership to the museum to ensure its preservation. The club was still in operation at the time and continued to host concerts, events arranged by the Mississippi Delta Blues Society of Indianola, birthday parties and other celebrations, and most notably, concerts by B.B. King during his annual “homecoming” visits to Indianola.

Founded in 1948, Club Ebony remained open continuously until the arrival of the pandemic in March 2020, hosting hundreds of stars of the blues and R&B world. Successive owners have made changes to the club to adapt to new demands from artists and the audience, and the recent renovations were set in motion to address serious structural problems with the south wall of the facility.

In addition to stabilizing the building, the renovation work involved adding a new catering kitchen, creating larger ADA-compliant bathrooms, doubling the serving size of the bar, building a large “green room” for visiting artists, and installing a sprinkler system and new exits/load-in doors. New features include a glass-enclosed sound booth, a ticket booth with a window, and cameras set up for livestream broadcasts.

The director of the B.B. King Museum, Malika Polk-Lee, says that renovating the club is “like coming back full circle.”

“My first major project after coming on as director in 2012 was renovating the club to make it more operable, and I’ve always wanted to get it to this point, so it has a sentimental value.

“For us, this is another part of our mission of fulfilling B.B. King’s legacy. He played at Club Ebony for fifty years, and the club was important enough to him to purchase it and entrust it to us. And since we are the preservers of his legacy, it was essential for us that its story would be told.

“Another aspect is the importance of the club to American musical history. So many artists were able to get their start here, keep alive their careers on the Chitlin’ Circuit and shape the development of African American music more broadly.

“And it’s also the story of the community. Club Ebony was not just a club, it was also a meeting place for the NAACP. It was a safe haven for talking about how to move the community forward, and a place where you could be around your own people and feel safe to be who you are and enjoy life.”

In addition to modernizing the facilities, the museum has been careful to preserve signature elements including the original stamped-tin ceiling and recessed neon lighting, as well as the glass block column designs of the bar and stage.

“We wanted to have a vintage look, but we also wanted to have modern features,” says Robert Terrell, the deputy director of the museum, who arrived there at the same time as Polk-Lee. “If we’re going to do something, we should do it right.”

One major difference is that the stage has been relocated.

“I always felt like the stage should be in the back, that way it’s convenient for everyone,” says Terrell. “When it was on the side, only so many people could see it. Now when you walk in the door you can see the stage.”

Sightline issues have also been addressed through purchasing new high tables and stools for the bar area.

“Another thing we thought about is that it’s such a historical place, so we wanted to tell its story,” says Terrell. A Mississippi Blues Trail marker out front summarizes its history, and a new addition to the Club is interpretive panels that address the Chitlin’ Circuit, the club’s ownership history, and dozens of stars who played there.

Since 2008 visitors to the museum have been able to tour Club Ebony, and larger tour groups often eat a meal of fried catfish while listening to local artists such as Mike Dennis. Immediately prior to the pandemic, the museum and Club Ebony were frequently on the itineraries of riverboats, including the American Queen, that dock in Greenville. Both river cruises and coach tours are quickly returning, and the new facilities allow for more comfortable visits.

“Now that it’s stabilized, it will stand for another seventy-five years,” says Terrell, who is also planning how it can be better utilized for the community.

The History of Club Ebony

Many Delta readers no doubt recall seeing B.B. King at the club during his annual “homecoming” visits to Indianola between the late 1970s and the 2010s. But the premier stars of jazz and the blues were performing there even before King’s career took off. The club opened at its present location on Hanna Avenue in 1948 and was owned by Johnny Jones, who had earlier run Jones’ Night Spot on nearby Church Street.

In a 1967 interview King, who recalled peeking in at bands through the windows of Jones’ Night Spot as a youngster, said that Jones “was really the guy that kept the Negro neighborhood alive, by bringing people in, like Louis Jordan…Johnny Jones was a very nice fellow, and he knew the guys on the plantations didn’t have any money during the week, but he would often let us in and we would pay him off when we came in Saturday.”

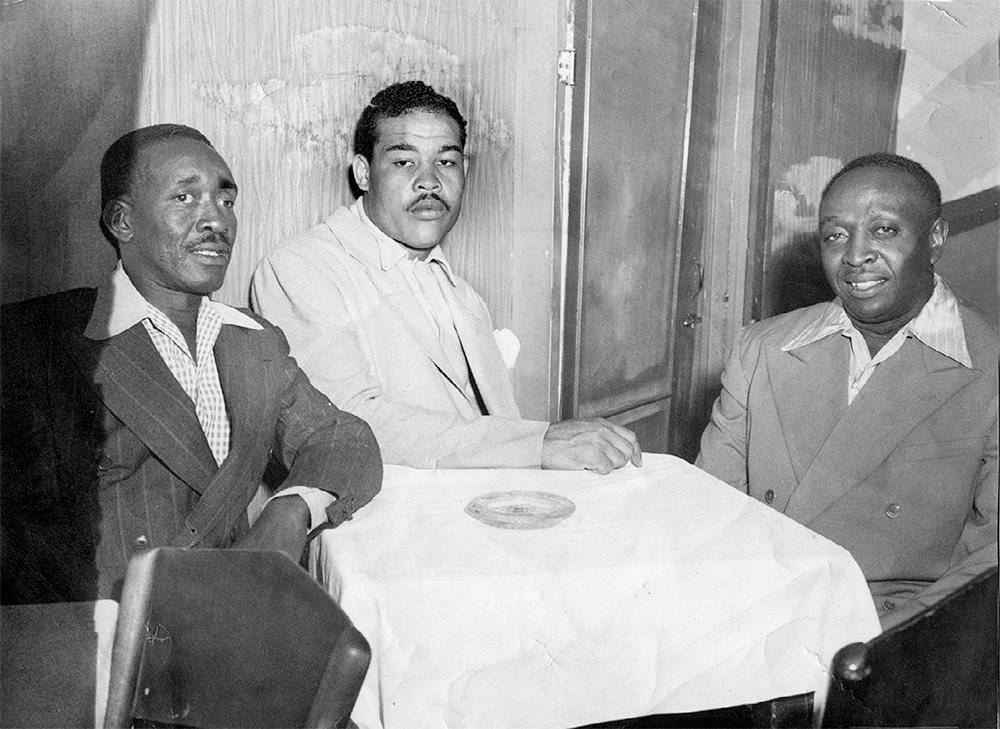

Club Ebony quickly became a mainstay of the Chitlin’ Circuit. The circuit originated in the mid-‘30s during the big band era, and took off in the more prosperous post-WWII years. Early visitors to Club Ebony included national stars such as the Count Basie Orchestra and King’s mentors including Louis Jordan and T-Bone Walker.

King, who moved from Indianola to Memphis in 1948, began playing at the club regularly following his breakthrough 1952 hit “Three O’Clock Blues.” In 1958 King married Sue Hall, the daughter of Club Ebony’s owner Ruby Edwards. They had met at the club, and were married in Detroit in a ceremony presided over by Rev. C.L. Franklin, a native of Sunflower County and the father of Aretha.

For decades Club Ebony boasted a lineup of the leading stars from the rhythm and blues world. These included Delta musicians who became stars of Chicago blues, including Jimmy Reed, Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson II, as well as pioneers of soul music, including Ray Charles, James Brown, and Clarksdale-born Sam Cooke.

In the wake of the Civil Rights movement, top African American artists had access to a much wider range of venues outside the traditional Chitlin’ Circuit, but Club Ebony remained particularly important into the 2000s for artists on the “soul blues/southern soul” circuit. These artists included many who were hitmakers on the R&B charts in the ‘50s through the early ‘70s, and later played relatively more old school music for Southern audiences—Bobby “Blue” Bland, Tyrone Davis, Johnnie Taylor, Denise LaSalle, and Bobby Rush. The club also featured local bands playing in the same style, notably the Ladies Choice band led by Bobby Whalen and David Lee Durham.

B.B. King became an international icon in the early ‘70s in the wake of “The Thrill Is Gone,” but returned regularly to his “hometown.” He was actually born in tiny Berclair in 1925, and moved as a teen to Indianola, where he married, became a tractor driver, and began playing gospel and blues.

In the early ‘70s he began coming back to Mississippi annually in June to perform at events celebrating the legacy of Civil Rights martyr Medgar Evers, and in the late ‘70s added “homecoming” events in Indianola. These eventually became formalized—he would play a family-friendly outdoor show in the afternoon, followed by a late night show at Club Ebony, a pattern he followed until the 2010s, when the outdoor show was on the grounds of the B.B. King Museum. He last played the club in 2013.

“It seemed like he knew it was his last show there,” says Terrell. “He stayed on the stage until 6:30 in the morning. He allowed his band to get off the stage, but he just stayed there and let fans take photos and talk to him.”

King died on May 14, 2015, and today visitors traveling between the museum to nearby Club Ebony pass King’s grave and “memorial pavilion,” which was unveiled in 2021 along with an expansion of the museum’s exhibit space.

2 thoughts on “Historic Club Ebony”

I’m a big blues fan. Very informative article. So much about Club Ebony and B.B. King I didn’t know.

Thank you

I’m THE RealBrownSugar and I open for BBKING at Club Ebony under Mrs Mary Shepherd and such a sweetheart and Mr King was so pleased that was a big high light for me