Langdon Clay made his initial visit to the Delta in 1971 on a cross country road trip from California to New York with his New England prep school friend, Lloyd Fonvielle. Fonvielle was from Wilmington, North Carolina, but neither he nor Langdon had ever been to the Deep South. They traveled in an MGB convertible, had sleeping bags and knew virtually no one, other than the couple of names given them by New York friends. After a pit stop in Memphis visiting Bill Eggleston, they somehow ended up in Rosedale, Mississippi. [Eggleston’s wife, Rosa Kate Dossett Eggleston, was from nearby Beulah.] Langdon, a then-fledgling photographer, was working on a series of photographs called A Day in the Life consisting of a picture of himself—either taken by a friend, stranger or, what would now be deemed as a “selfie,” a self-portrait— every day for an entire year. The photograph for October 10, 1971, taken by Lloyd Fonvielle, depicts Langdon on the front porch of the Colonial Inn in Rosedale, a landmark river hotel that later burned. [Historian Adrienne Beard notes: The Colonial, near the levee, was a frequent stop for whiskey boats, or “blind tigers” as the locals called them. Mississippi bootleggers outfitted small riverboats with casks of illegal corn whiskey and docked them behind the inn.] The thing Langdon says he remembers most succinctly about that trip was seeing open fields of cotton for the first time and the smell of defoliant, which for many years afterward he assumed was the smell of cotton. He also recalls meeting a Delta State student who, after confiding his mother had recently discovered his pot in his sock drawer, invited them to sleep on his dorm room floor.

his New England prep school friend, Lloyd Fonvielle. Fonvielle was from Wilmington, North Carolina, but neither he nor Langdon had ever been to the Deep South. They traveled in an MGB convertible, had sleeping bags and knew virtually no one, other than the couple of names given them by New York friends. After a pit stop in Memphis visiting Bill Eggleston, they somehow ended up in Rosedale, Mississippi. [Eggleston’s wife, Rosa Kate Dossett Eggleston, was from nearby Beulah.] Langdon, a then-fledgling photographer, was working on a series of photographs called A Day in the Life consisting of a picture of himself—either taken by a friend, stranger or, what would now be deemed as a “selfie,” a self-portrait— every day for an entire year. The photograph for October 10, 1971, taken by Lloyd Fonvielle, depicts Langdon on the front porch of the Colonial Inn in Rosedale, a landmark river hotel that later burned. [Historian Adrienne Beard notes: The Colonial, near the levee, was a frequent stop for whiskey boats, or “blind tigers” as the locals called them. Mississippi bootleggers outfitted small riverboats with casks of illegal corn whiskey and docked them behind the inn.] The thing Langdon says he remembers most succinctly about that trip was seeing open fields of cotton for the first time and the smell of defoliant, which for many years afterward he assumed was the smell of cotton. He also recalls meeting a Delta State student who, after confiding his mother had recently discovered his pot in his sock drawer, invited them to sleep on his dorm room floor.

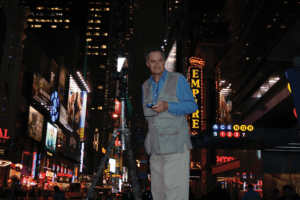

When Langdon returned to New York City, he began the project 16th Street, photographing his block between 6th and 7th Avenues every day for two months. Working on photographic series became an obsession, and from 1974-76 he traversed the streets of Manhattan at night looking for cars that “matched” their backgrounds. This color work was shown in 1978 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in Lo ndon and the Corcoran Gallery/ Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D. C., and was featured in an article in Newsweek called “They Park By Night” as well as Zoom, a French photo journal. The New York Times sent him to photograph the Natchez Pilgrimage, which led to work at Rolling Stone (where he photographed Randy Newman, John Prine, Levon Helm and many other musicians), New York and a variety of magazines. Over the course of three months in 1979, his personal project was using an 8×10 view camera at night, photographing 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues; The 42nd Street Panorama, as it became known, remains a key document of Times Square at its seedy best, especially since the area has become more like Disney World in its current touristy (and much safer) incarnation.

ndon and the Corcoran Gallery/ Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D. C., and was featured in an article in Newsweek called “They Park By Night” as well as Zoom, a French photo journal. The New York Times sent him to photograph the Natchez Pilgrimage, which led to work at Rolling Stone (where he photographed Randy Newman, John Prine, Levon Helm and many other musicians), New York and a variety of magazines. Over the course of three months in 1979, his personal project was using an 8×10 view camera at night, photographing 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues; The 42nd Street Panorama, as it became known, remains a key document of Times Square at its seedy best, especially since the area has become more like Disney World in its current touristy (and much safer) incarnation.

By 1982, he had switched over to architectural photography, gotten a book deal to photograph Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and focused on a career working for various architects and “shelter magazines,” such as Architectural Digest and House and Garden. He and his new wife (yes, dear readers, it was I) were making pilgrimages from New York in the summers and holidays to visit her family in the Mississippi Delta. Though they moved to Sumner in 1987, Langdon was still flying out of Memphis weekly, working on books like From My Chateau Garden in Burgundy, France, and photographing houses, gardens, and food all over the world.

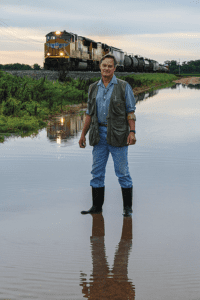

In contrast to his commercial work, he began to be drawn to photographing life in the Delta. One of his ongoing projects for almost twenty-five years has been Landscapes, Cityscapes, consisting of juxtaposing focal planes of the landscape with the human or man-made thing. He describes this work as “combining the natural landscape with several layers of objects and shadows, balancing form and content. It’s like a stage set with dancers, with a foreground, background and midfield.” Inspired by Italian Renaissance painter Piero della

projects for almost twenty-five years has been Landscapes, Cityscapes, consisting of juxtaposing focal planes of the landscape with the human or man-made thing. He describes this work as “combining the natural landscape with several layers of objects and shadows, balancing form and content. It’s like a stage set with dancers, with a foreground, background and midfield.” Inspired by Italian Renaissance painter Piero della  Francesca and the 17th century Dutch painter Vermeer, he “records daily domestic life distilled through color and light.” He has for the last few years been retracing the steps of Paris photographer Eugene Atget (1857-1927.) Because Paris is a city whose architecture has for the most part remained intact — it was not, for example, bombed during World War II — many of the streets, statues, fountains and parks that Atget photographed a hundred years ago are virtually unchanged. Langdon’s photographs are in color, and Atget’s were, of course, in black and white, but the contrast of how things looked then contain often strikingly similarities to today’s Paris.

Francesca and the 17th century Dutch painter Vermeer, he “records daily domestic life distilled through color and light.” He has for the last few years been retracing the steps of Paris photographer Eugene Atget (1857-1927.) Because Paris is a city whose architecture has for the most part remained intact — it was not, for example, bombed during World War II — many of the streets, statues, fountains and parks that Atget photographed a hundred years ago are virtually unchanged. Langdon’s photographs are in color, and Atget’s were, of course, in black and white, but the contrast of how things looked then contain often strikingly similarities to today’s Paris.

The main thing Langdon says he wants to do is leave a record of what these places, whether Paris or the Mississippi Delta, looked like in our particular time period. “In ten years or one hundred years, through photographs we’ll see what was here. It is too much hubris to say that this was what life was like, but it’s not too much to say this was what life looked like.”