By KATIE TIMS

Courage and perseverance have kept this historic Delta home in the family for two hundred years

Highway 61 has plowed its way through fields, towns, what used to be yards, and whatever was in its rambling path from Memphis to Vicksburg. But at Nitta Yuma, a little baby girl turned the road all by herself. More on that later.

Nitta Yuma is about forty-five minutes north of Vicksburg, where the highway veers gently to the left and manicured grounds with white fences abound. It’s impossible to miss. An impressive antebellum home and charming chapel grace the west side of the highway, while genteel, tree-lined grounds, log cabin and pretty white house adorn the left. Delightful old buildings, in various stages of disrepair and restoration, dot the landscape on both sides.

At the speed limit, Nitta Yuma is a historic Mississippi plantation that has been held together by strong family bonds—black and white, North and South—with mutual respect, devotion, sacrifice, sorrow, joy, hardship, progressivism, and stubborn resilience. That is what has kept Nitta Yuma alive and in one family for nearly two hundred years.

To really understand, one has to stop where the road bends.

The Place

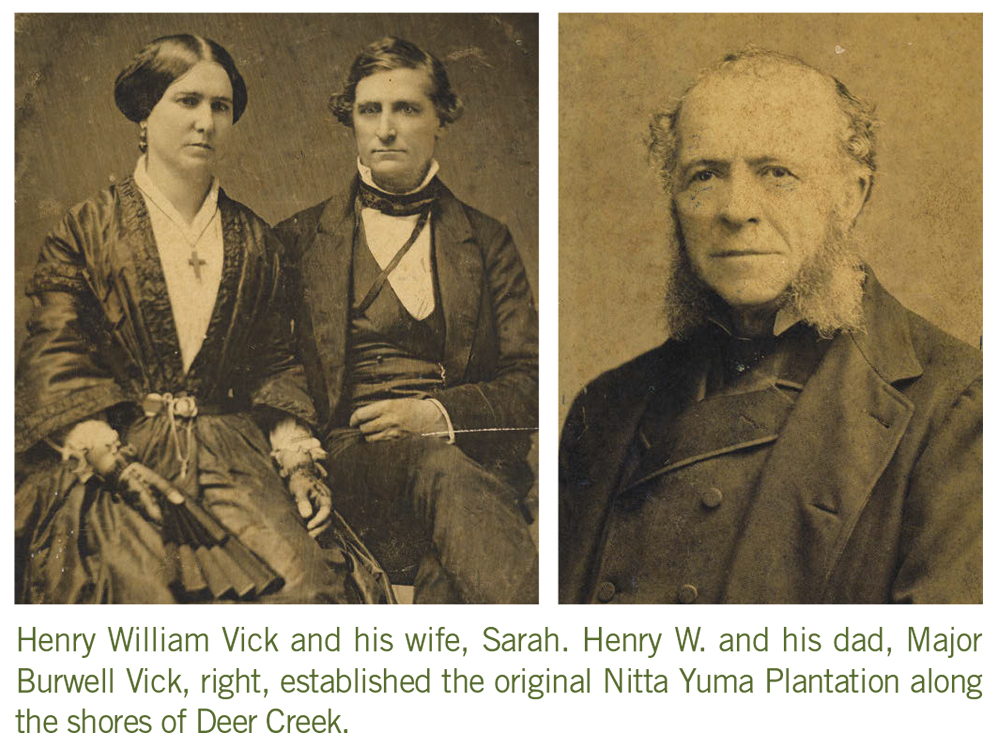

Nitta Yuma is what remains of a larger plantation carved from Choctaw Indian land in the early 1800s. Major Burwell Vick—the founder of Vicksburg—and his two brothers, Thomas and Newit, migrated from Virginia to Mississippi sometime between 1803 and 1810. Immediately, they began buying land for the cultivation of cotton.

Burwell had four children. He and his oldest son, Henry William Vick, pushed the family’s holdings north into the unsettled, wild, swampy Delta woodland between the Yazoo and Mississippi Rivers. The race was on to acquire the best land for growing crops, acreage with navigable waterways, and enough elevation to stave off annual floodwaters. In 1829, the Vicks used family jewels to purchase land that would become known as Nitta Yuma.

Family history reports that Choctaw Indians guided Burwell and Henry W. along Deer Creek. At one stop, a little Indian boy got out of the boat and scampered up the creek’s embankment. He pointed to the ground and shouted, “Nitta yuma! Nitta yuma!” (“Bear track! Bear track!”) That’s where the Vicks chose to build their plantation.

Nitta Yuma’s history could fill a book—and it has. The late Dorothy Phelps and her husband, Henry Vick Phelps II (Henry W. Vick’s great-grandson) wrote and published Nitta Yuma – King Cotton in the 1970s. Two of her children, Henry Vick Phelps III and Carolyn Phelps May, still live at Nitta Yuma with her husband, Woody. Their other two children, Irene Phelps Terry and Vicki Phelps Domin, live in Brentwood, Tennessee, and Vicksburg, Mississippi, respectively. There’s also a seventh generation directly tied to Nitta Yuma: Henry Vick Phelps IV, 33, who also lives at Nitta Yuma; and Cooley May, 42, who resides in Houston, Texas.

The Nitta Yuma plantation has defied the odds—almost all of it has stayed in one family from the start until now, two centuries long.

Marriage Bonds

At the time Nitta Yuma was formed, cotton growers were at the mercy of governmental policies and economic conditions that exerted significant impact on agriculture and banking. Landowners had to weather the extreme ups and downs of cotton prices, plus weave their way through droughts, floods, and everything in between. Headwinds cascaded in 1849, and the family almost lost Nitta Yuma. Henry W. was forced to sell the plantation at a public auction in order to settle a $45,988 promissory note.

His wife, Sarah Pearce, was from a prominent and wealthy family in Louisville, Kentucky. Thanks to a law passed in 1839 that allowed married women to own land, Sarah was able to purchase back Nitta Yuma for $30,858. But that law also stipulated that women could not “control” land. So Sarah designated Nitta Yuma to a trust deed and then signed control over to her husband by appointing him as the trustee.

That was not the last time an outsider would save the Nitta Yuma legacy. It happened again after the Civil War when a doctor from Ohio married into the family.

The Duel

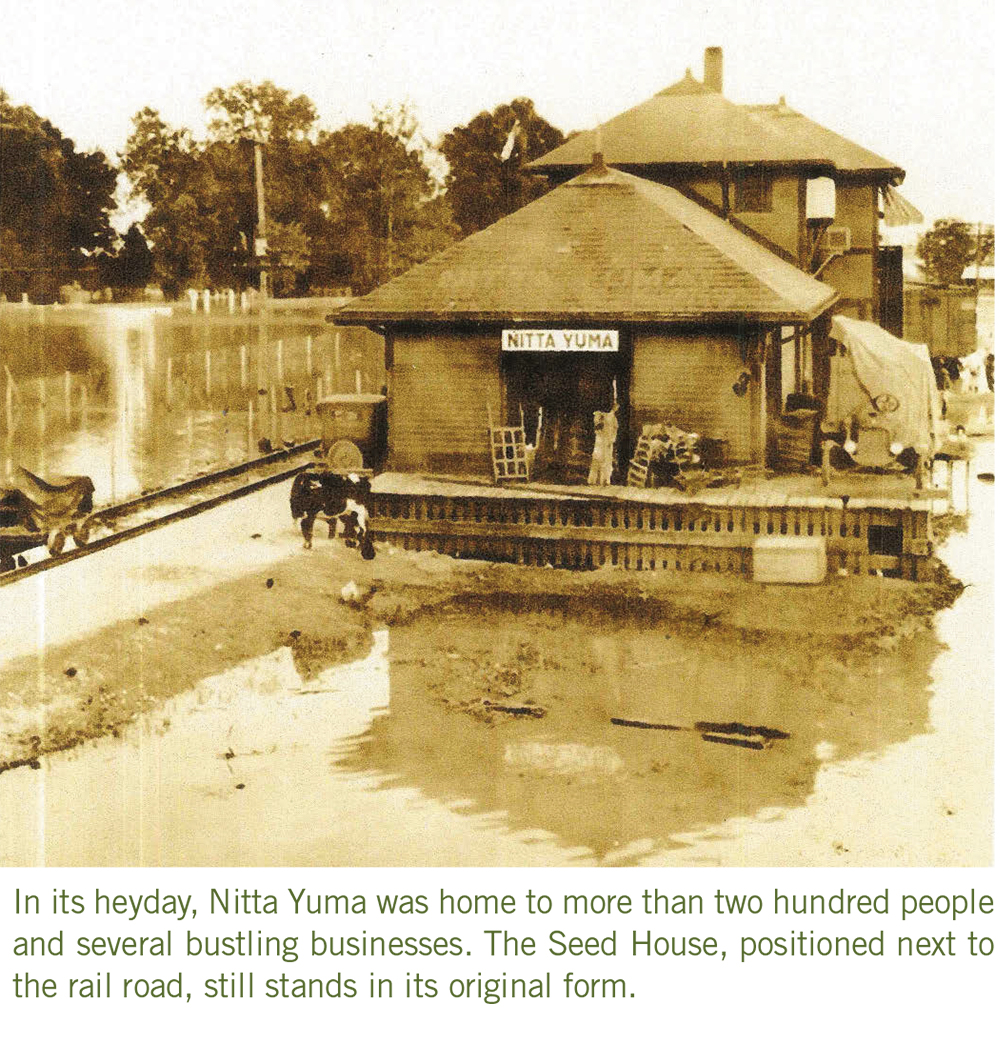

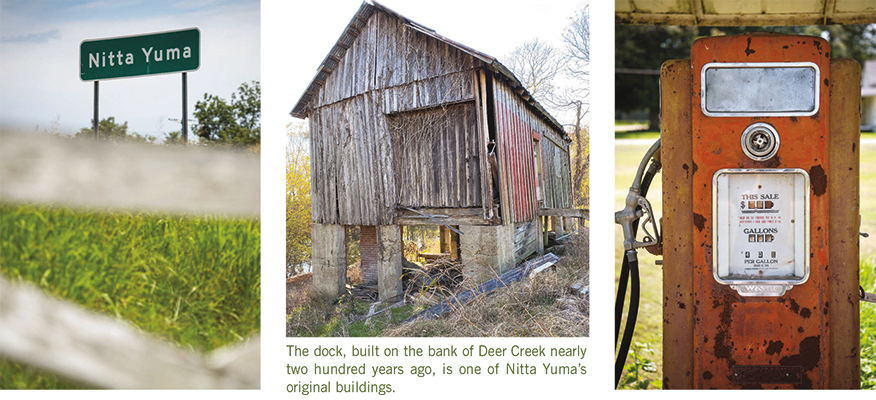

Henry W. and Sarah divided their time between their grand residences in Vicksburg and Louisville. Nitta Yuma and the other plantations were still remote locations with very little housing and no social structure. Nitta Yuma had the bare basics—a log cabin, dock on Deer Creek, seed house, store, and the various outbuildings needed to operate plantation business.

By then, the seeds for family success were already planted.

From his own crops in the Mississippi Delta, Henry W. developed a quality, high-producing cotton seed that was put on the market around 1843 as “100 Seed Variety.” He was regarded as one of the most successful planters in the South, thus earning the local nomenclature, “King Cotton.”

Henry W. and Sarah had five children—three sons and two daughters. The oldest of these, Henry Gray Vick, was just fifteen when his mother collapsed while playing the organ at church. She died later that day. Sarah’s will stipulated that her holdings in Mississippi and Kentucky be divided among her four surviving children. Henry Gray received the northern portion of Nitta Yuma, an area known as Vickland Plantation.

Henry Gray was a bright, dynamic, sporting young man naturally destined to take over the family businesses. He met Helen Johnstone, who came from the Annandale Plantation near Madison, and after six months of courting, they were to be married in May 1859. Sadly, that never happened.

Henry Gray had a trusted servant named Jake with whom he developed a very close bond over the years—much like father and son. While attending the bachelor party at Vickland, one of the party-goers had a brush-up with Jake over the way a horse was saddled. James Stith, who had been friends with Henry Gray since childhood, demanded the servant be punished. Henry Gray refused and then defended Jake’s honor, which enraged Stith. Their friendship was done.

The situation might have concluded there, but the two men bumped into each other while Henry Gray was on a business trip to New Orleans a few days prior to the wedding. One thing led to another, and on May 17, 1959, Henry Gray and Stith found themselves in a duel. Henry Gray, who had promised Helen never to kill a man, shot his gun into the air; Stith shot for keeps and killed Henry Gray.

Friends escorted Henry Gray’s body back to Nitta Yuma, where he was unloaded at the dock. At that time, Deer Creek was navigable to the Mississippi River—from the north through Lake Bolivar and from the south through the Yazoo River. Steam-powered boats were the main source for the transport of people, commodities, and supplies. (The railroad did not arrive until around 1886.)

James Stith was killed in the Civil War, at the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863.

From Vick to Phelps

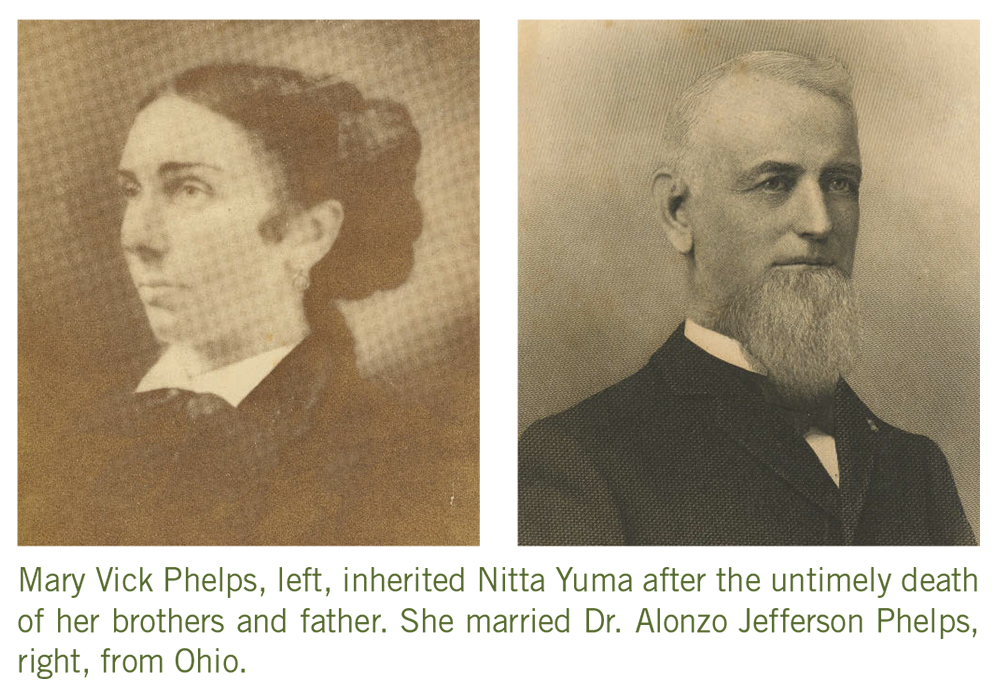

In his will, Henry Gray left the northern portion of Nitta Yuma, known as Vickland Plantation, to his intended bride, Helen Johnstone. The rest of the family’s estate was to be divided between his siblings, George and Mary. Heartbreak over Henry Gray’s death and the threat of Civil War took a toll on their father, and Henry W. Vick died in January 1861. George died suddenly from a heat stroke a few months later, making Mary the sole heir of Nitta Yuma.

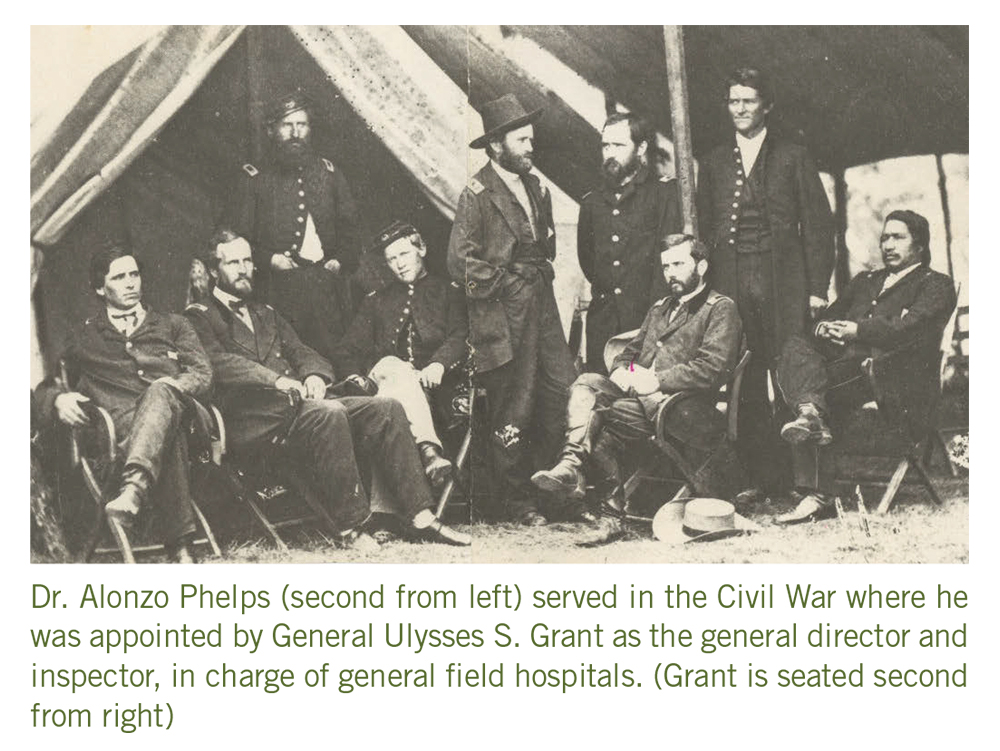

While in Louisville with her aunt, Mary was introduced to Dr. Alonzo Phelps, a dynamic young physician from Ohio. They courted until Alonzo left to serve in the Civil War where he was appointed by General Ulysses S. Grant as the general director and inspector in charge of general field hospitals. Mary and Dr. Phelps corresponded back and forth, and they married in 1865.

The couple moved to Mississippi and took over a financially challenged Nitta Yuma. Dr. Phelps rolled up his sleeves and assumed the leadership, thus enabling the plantation to survive.

“And he kept the carpetbaggers away,” says Henry Vick Phelps III.

Dr. Phelps and Mary had four children: Mary, who married Count Renato Caselli from Italy; Nannie, who married a Scotsman Peter George; Ellen, who married Dr. Robert Crump from North Carolina; and Henry Vick Phelps, who married Helen Smiley from St. Louis.

Dr. Phelps continued to run Nitta Yuma and serve on the Mississippi Levee Board until his death in 1897. Mary died in 1901. Nitta Yuma was divided among their four children. A map still exists with the hand-drawn divisions that were assigned by a drawing of names. Henry Vick Phelps ended up with the main house and grounds near the road.

Bend in the Road

In a way, the bend in Highway 61 is testament to Nitta Yuma’s trek to modernity with family reverence in mind.

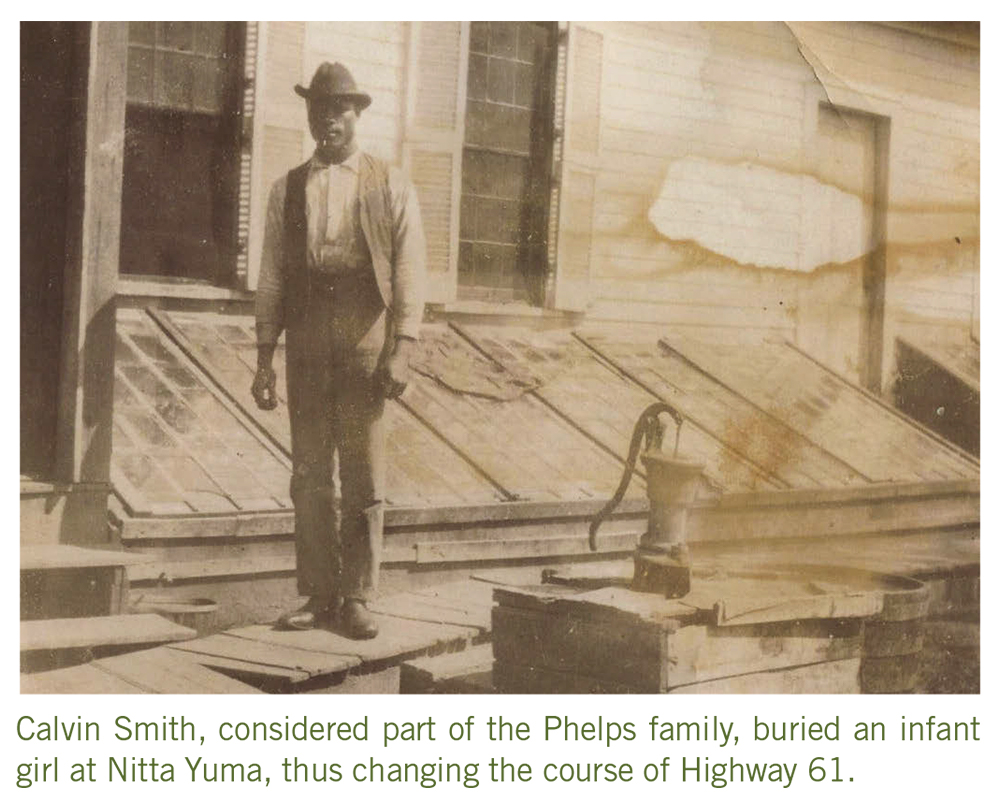

Around 1903, Helen Phelps was riding her horse a short distance to the Mont Helena plantation when she very unexpectedly went into labor, as she did not realize she was pregnant. Helen galloped back to her house at Nitta Yuma and delivered premature twin daughters, the first of which passed away as the second was being born. Calvin Smith, the family’s longtime trusted employee and friend, was asked to bury the deceased baby girl.

“I started to carry her over to the old cemetery, but I thought, ‘No,’” Calvin recalled in the Nitta Yuma – King Cotton book. “I’d heard some talk about widening the road. Then I wondered about placing her over there on the north side of this front yard. That would be by the old dirt road that leads to the mule lot.”

But that backyard would eventually become the front yard. Deer Creek was dammed, and the water receded. The mansion burned, and what had been the carriage house was converted into a home that faced west.

According to Vick-Phelps family history, civil engineers came through the Delta in the 1920s, to survey land for the future Highway 61. At Nitta Yuma, the most direct line sent the road straight along the existing railroad, but that meant the highway would go over the little girl’s grave. So the engineers opted to alter the course just a smidgen, thus creating the bend in the road at Nitta Yuma.

Yesterday Is Today

There are two hundred years’ worth of yesterdays at Nitta Yuma, a real treat for all of us today. Visitors are welcome at Nitta Yuma, and either Henry Vick Phelps III, Henry Vick Phelps IV, or Carolyn May are available to give tours and tell the family’s history. You can visit the Nitta Yuma Facebook page to learn more and communicate with the family.

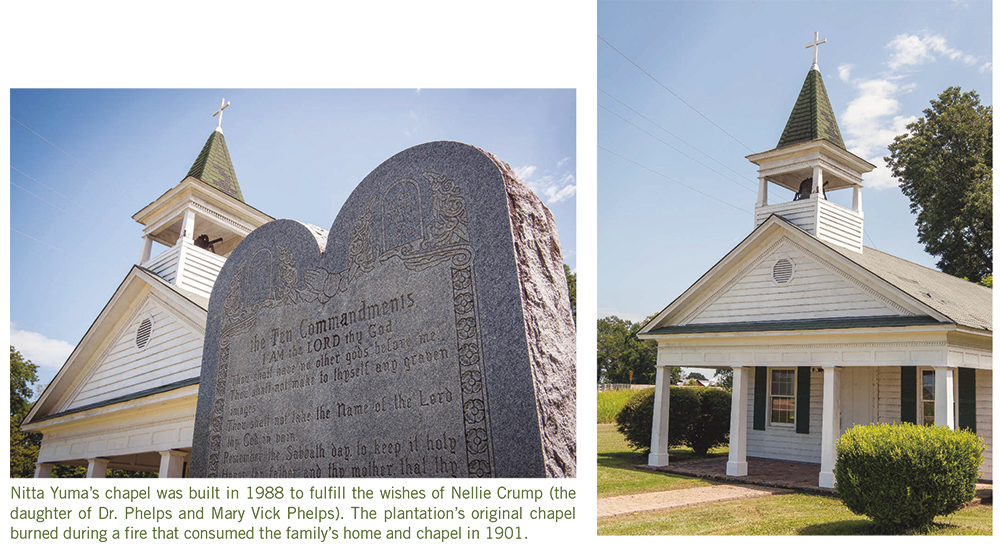

Numerous buildings, spanning 200 years, grace the grounds at Nitta Yuma. The chapel was built in 1988 to fulfill the wishes of Nellie Crump (the daughter of Dr. Phelps and Mary Vick). The plantation’s original chapel burned during a fire that consumed the family’s home and chapel in 1901. History is paramount in this new church. The doors are from the Vick family home in Vicksburg and the pews from the old Chapel of the Cross Church, the African American church in Nitta Yuma. Also, Henry Vick Phelps II and his wife, Dorothy, were laid to rest in a mausoleum at the back of the chapel.

The Cameron House is actually an antebellum home from the Cameta Plantation, just south of Nitta Yuma. Henry Vick Phelps II purchased the abandoned house as an anniversary gift for his wife, Dorothy, in 1976. The building was sliced into sections and moved, piece-by-piece, to Nitta Yuma. Today, the Cameron house is beautifully renovated and filled to the brim with furniture, décor, and tools that have been in the Vick/Phelps family for generations.

Mary Phelps married into the Italian aristocracy and lived her life in Italy. Her son, Renato Caselli II, moved from Italy to Nitta Yuma. He opened a store, built a home, married an American girl, and had a family. One of his sons, Carlo, is a retired farmer who still lives in Nitta Yuma.

A few years ago, Carolyn was picking up her mail and she happened upon a young couple from Belgium. Music aficionados, they were driving along the Blues Trail that stretches from Memphis to New Orleans.

One conversation led to another, and pretty soon Neelke and Gerrit Leroy became part of the Nitta Yuma family. They were married in the plantation’s chapel and held their reception in the plantation’s old post office. Now, the Leroys hope to one day relocate to the United States and renovate the Caselli Store.

Authenticity on Display

In total, there are nine antebellum buildings at Nitta Yuma, along with several others dating back at least a century. At one point in the 1930s, Nitta Yuma had more than two hundred residents. Now, its population is about twenty. Some structures, such as the landing dock at the edge of Deer Creek, date back to the very first days of the plantation and remain in their original locations. Most of the others have been relocated to the Nitta Yuma grounds—including the gorgeous 1820s log cabin situated next to the family’s main residence on the east side of the road.

“Every time I came home it seemed as if Daddy had moved another house,” Carolyn says with a laugh.

“Yeah, he got good at it.” Henry Phelps II agreed. “It’s amazing what you can move with two telephone poles!

The stately white house you see now on the east side of the road was actually a carriage house. The original Vick family home—built in the early 1800s—faced east, toward Deer Creek. That house burned and another was built in its place, which then burned in 1901. Instead of spending the money to build the twenty-room mansion he dreamed of, Henry Vick Phelps started renovating and adding on to the structure that housed the carriages, and it still serves as the family’s primary residence. In the 1950s, Henry Vick Phelps II and Dorothy renovated that home using materials recovered from the razing of two family homes in Vicksburg. The columns you see today are examples of that grand endeavor.

Henry and Dorothy, along with Henry’s aunt Nellie, were adamant that Nitta Yuma’s history be preserved.

“My grandparents collected antiques, and they wanted to set up this entire town as a museum,” Cooley says.

Dorothy’s doll collection, which numbers at least three thousand, is housed in a former post office/general store. Henry’s train collection chugs away in a building by the family home. And all the family’s documented history—including letters, journals, maps, publications, and photos—are in Carolyn’s care. Henry Vick Phelps III takes care of the grounds and does his level best to keep up with building maintenance.

“Every day, when I got back from school, my grandmother would be in a different building, and she would tell me about every piece of furniture,” the son, Henry Vick Phelps IV, recalls. “We’d sit in the kitchen for the longest time and talk about the plantation and how to move forward with it, how to improve it. She knew how to inspire you.”

2 thoughts on “Nitta Yuma”

I do enjoyed reading this history of Nitta Yuma!!

I have lived in this Delta my entire live and did not know all this history.

Thank you for sharing this with your readers.

Since I first saw Nita Yuma I have been fascinated, and this is certainly the only in-depth account I have run across of this plantation – or is it 5 plantations 🙂 ? Thank you. I am hoping to send this to several friends. Several years ago Henry Waterer of Tchula and I enjoyed the play very much – about the bride with Mt. Helena, Annandale, and Nita Yuma connections. Thank you. You have a lovely magazine, and I particularly enjoyed the mantel fall decorations.