by HANK BURDINE

How a small Arkansas Delta town helped change the course of American literature

It was cold in Paris in the winter of 1924-25. Ernest Hemingway was living in an apartment with his wife Hadley and young son, John (Jack, aka Bumby), at 113 rue Notre-Dame des Champs. He was eking out a living while writing for periodicals, having published several books including Three Stories and Ten Poems and Men Without Women, and was finishing up The Sun Also Rises. He had begun working on his book A Farewell to Arms. The Hemingways had become friends with the bohemian literati group of authors living or spending time in Paris: John Dos Passos, Archibald MacLeish, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Ford Maddox Ford, and Gertrude Stein, among others. They later became known as the “lost generation of American expatriate writers.” Gertrude Stein would state, “Paris is where the twentieth century was.”

During the Spring of 1925, at a tea given in Paris by friends, the Hemingways were introduced to Pauline and Ginny Pfeiffer, two charming sisters from Piggott, Arkansas. The older of the two, Pauline, was a fashion writer for Paris Vogue and quite nattily dressed. The two sisters, through other gatherings and ski trips to Schruns, Austria, and bullfighting soirees in Spain, became close friends with Hadley; all the while, Pauline was keeping a very special eye out for Ernest. And as well could be imagined, a break-up and eventual divorce of Ernest and Hadley came to pass. Ernest Hemingway and Pauline Pfeiffer were married in the Catholic Church of Passy in Paris on May 10, 1927. With Pauline’s six-thousand-dollar annual stipend from her family, Ernest Hemingway no longer had to worry about food on the table or heat in his apartment. So with Bumby safely tucked away with his mother and Pauline pregnant, it was soon time to leave Paris. The newly wedded Hemingways booked a cabin in April of 1928 on the Orita from Marseilles, France, to Havana, Cuba, and then on to Key West, Florida, where they were to pick up a brand-new yellow Model A Ford Roadster given to them as a wedding gift from Pauline’s rich Uncle “Gus” Pfeiffer. From Key West, after vacationing for about six weeks, they were to ferry themselves in their new sports car up-keys to Miami and on to Piggott, Arkansas. Once there, Pauline could show off her new prize, the writer Ernest Hemingway, and her own noticeably bulging belly.

As the ferry approached Key West, with the smoke from its smoldering garbage dump visible and the radio towers emerging out of the sea, which would later become instrumental in Ernest’s navigation to and from Bimini and Cuba, the low-slung unpainted wooden conch houses became noticeable. Was this the place that John Dos Passos had recommended his friend Hemingway to go and spend some time in order for “Old Hem… to dry out his bones”? It was hot; Ernest was sweating in his starched collar and necktie, and Pauline was quite uncomfortable in the heat. What made Ernest really hot was the fact that there was no car waiting for them on the docks once they cleared customs. A delay in shipment of the car from Miami caused the dealership to put the couple up in an apartment above their showroom. When the car from Uncle Gus arrived a week later, Ernest began venturing out to fish off of piers and soon met local luminaries who realized he wasn’t just a bum on the run in his cutoff canvas shorts, dirty tennis shoes, pullover cap, and smelly fish-stained shirt or another bootlegger waiting on a boatload of illegal whiskey to come ashore from Cuba to be unloaded. In a book by Stuart McIver titled Hemingway’s Key West, Charles Thompson, a member of one of Key West’s most prevalent and influential families, told his wife, Lorine, “George Brooks (prosecuting attorney) sent him by. Says he likes to fish and that I might take him out. Says he’s written a couple of books.” By April of 1928, the twenty-nine-year-old Hemingway had published six books and was beginning to like the very laidback easy-going lifestyle of Key West.

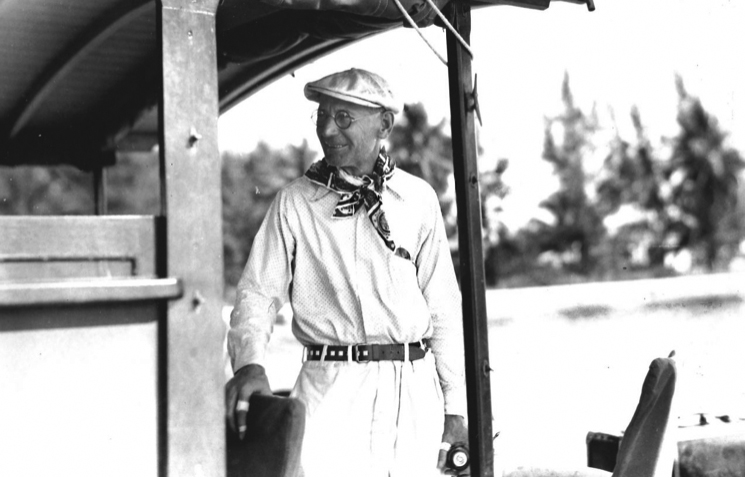

Pauline’s father, Paul Pfeiffer, came down to meet his new son-in-law and was ensconced in the town’s predominant skyscraper, the seven-story Key West Colonial Hotel. It was hot and soon Pauline began trying to get them all to leave and go to Piggott where it was at least not as hot! Ernest resisted and eventually let Pauline take the train homeward to Piggott. Paul Pfeiffer stayed, and Ernest invited a gang of friends down to join him and a local bunch of cronies he had termed the “Mob.” Once gathered, they began carousing about, drinking at the local hangouts and speakeasies, eating in local diners, and fishing around the islands. Ernest Hemingway was really beginning to like what he saw in what he later called the “St. Tropez of the Poor.” But it was time to go north with his new friend and father-in-law Paul Pfeiffer riding shotgun in a new Ford Roadster. Before he left, Ernest asked Lorine Thompson to find him and Pauline a house to rent for the next season.

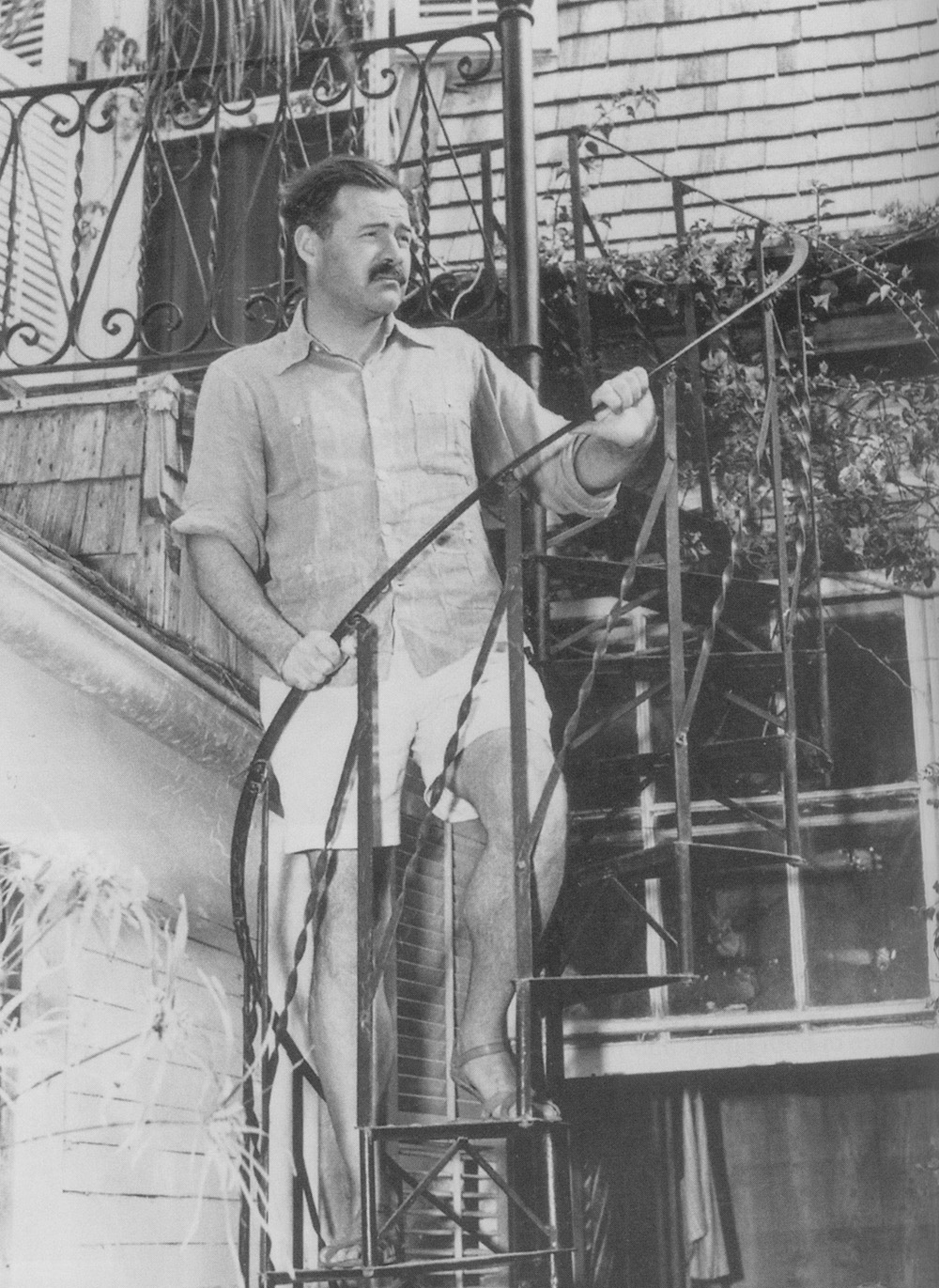

Patrick Hemingway was born in Kansas City and that winter the Hemingways returned to Key West with Ernest writing in the mornings and fishing or carousing in the afternoons. They liked the pace of Key West and began looking around for a permanent house, as Ernest told Charles Thompson, to “hang my hat.” “You don’t have a hat,” replied his good friend. “Well by God, I’ll buy one the day I move in.” By that time, Pauline and Lorine Thompson had already been looking for a house to buy. Returning to a dilapidated old stone house at 907 Whitehead Street that Lorine had once called “a miserable wreck of a house,” Pauline soon saw potential in what she had once described as “a damned haunted house.” Escaping the heat of Key West in the summer, the Hemingways would travel to Piggott, Arkansas, on the way back and forth to the Wyoming L-BAR-T Dude Ranch where Ernest would write in the mornings and hunt in the afternoons. During these forays, Ginny Pfeiffer decided to fix up the barn at their family home in Piggott for her sister’s new family to stay in and to allow Ernest a quiet place to write.

The Hemingways second child, Gregory, was born in November of 1931, again in Kansas City. That same year they had decided to buy the “damned haunted house” on Whitehead Street because it had potential with a large living space, a big yard for two children, and a secluded location. Built in 1851 in the style of a large Spanish estate, it had a two-story carriage-house outbuilding that could be converted into a writing workroom. Uncle Gus wrote a check for eight thousand dollars, paying off several past-due mortgages to the local bank and conveying the property to Ernest Miller Hemingway, 4 Place de la Concorde, Paris, France c/o Guaranty Trust Co. of New York City. Ernest Hemingway’s Paris days were over, and with a new address, 907 Whitehead Street, he now had a place to hang his hat in Key West, Florida. American literature was about to change.

The Key West years

James McClendon states in his book Hemingway in Key West, “It is my belief that these years, 1928 to 1940, the dozen years Ernest Hemingway spent as a permanent or somewhat resident in the small seaport town of Key West, Florida, were the most important years of his life.” Whether it was his literary achievements accomplished during this time or the building and solidifying of the “Papa Myth,” those years made him who he turned out to be. And not much of it could have happened, or happened as easily, without the support and backing of the Pfeiffer family. Rooted in the pharmaceutical business, the Pfeiffers were major stockholders in the Hudnut Cosmetics Company and other related businesses. During a train breakdown in Piggott, Arkansas, Paul Pfeiffer decided to get out and walk around. He saw fields of lush Arkansas Delta dirt being cleared and farmed, and he saw opportunity. The Pfeiffers began accumulating land and real estate eventually owning about sixty-five thousand acres of prime cotton ground, the Piggott Custom Gin Company, the local bank, and most of the town. The Pfeiffer’s fiefdom reached far and wide, and their family’s desire was to take care of one another. Gus Pfeiffer and his wife lost one child and bore no more children, so he lavished his extended family with gifts of houses, cars, and money. Uncle Gus, as he was known, took a liking to the swashbuckling, hard-drinking, acclaimed, world-renowned writer and devoted hunter and fisherman that had married his niece, Pauline. Regarding Uncle Gus, John Dos Passos wrote, “Ernest fascinated him, hunting, fishing, writing. He wanted to help Ernest do all the things he’d been too busy to do while making money.” He admired him so much that when Hemingway talked about an African safari he would like to put together, Uncle Gus financed it to the tune of about twenty-five thousand dollars in the middle of the Depression (around five hundred thousand to six hundred thousand in today’s dollars, if not more). From that safari, guided by one of Africa’s most famous hunters, Phillip Percival, and including Pauline and Charles Thompson, would come several best-selling books and numerous magazine articles, Green Hills of Africa and The Snows of Kilimanjaro included.

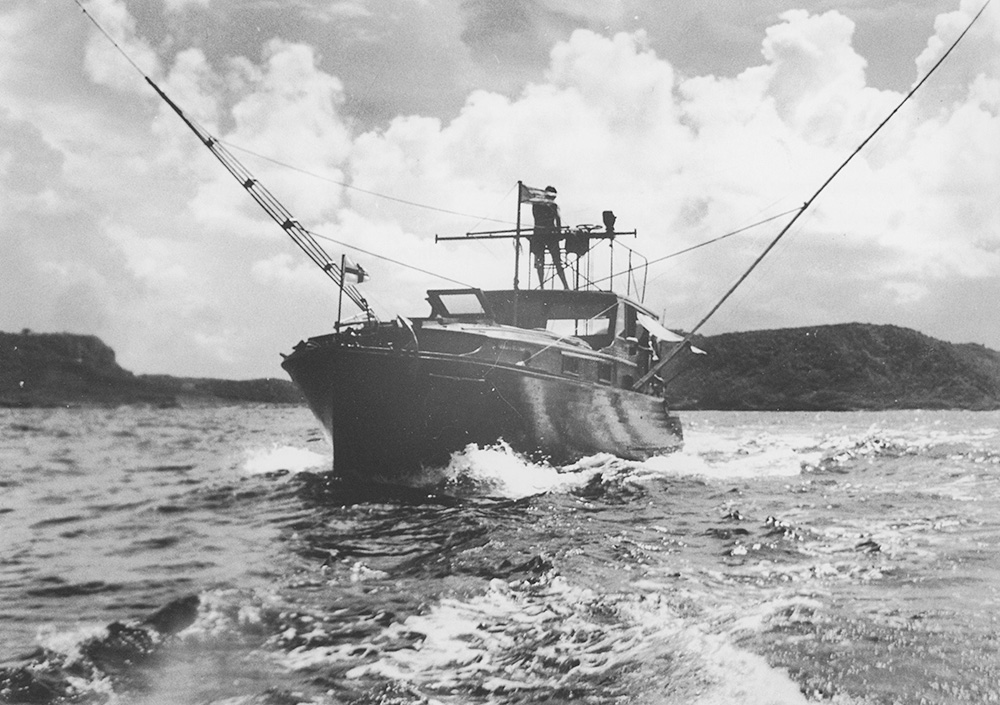

Immediately upon returning to New York from Africa, after a stopover in Paris, Hemingway went to the offices of the newly formed gentleman’s magazine Esquire and received an advance of three thousand dollars for future articles mostly based on his recently completed safari. He then went directly to the Wheeler Shipyards and placed his advance as a down payment on a thirty-eight-foot power yacht built to his own specifications to cost him $7,400. James McClendon stated, “He would name the craft Pilar. It would be a sleek, black-hulled vision of grace in the water, trimmed out in brilliant mahogany, and it would occupy most of Ernest’s free time for the rest of his life.” How much of this would have been possible without the financial support of good ole Uncle Gus and the Pfeiffer family?

“Cap, I hear you are looking for a driver.”

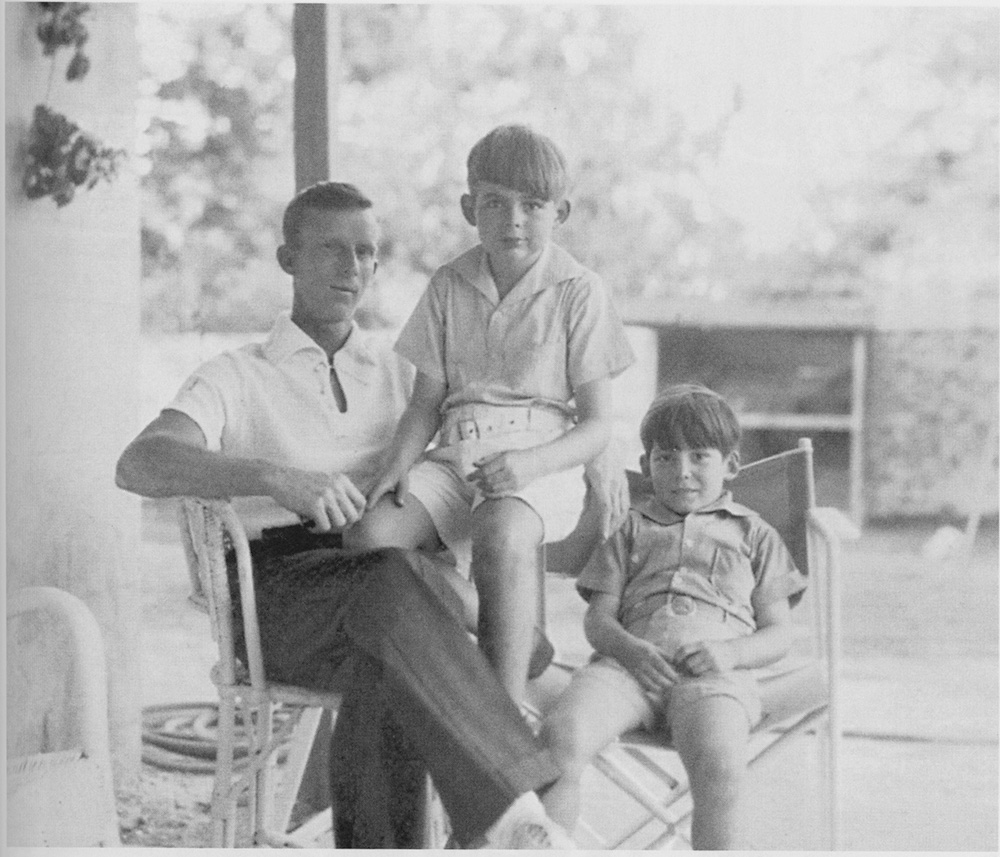

During one of the return trips from out West, while staying in the newly refurbished barn in Piggott, a fire started in a damper, and manuscripts and guns and belongings were tossed out the windows amid the flames. A young furniture maker named Toby Bruce from Piggott, whom Ernest had previously met, showed up to help collect and dry out the manuscripts. They became friends shooting trap and hunting together. A few years later on a dusty hot drive up from Florida, Ernest Hemingway put word out in Piggott that he was looking for someone to help drive. Showing up in a pinstriped suit, black shoes, and a fancy tie and sporting a Homburg hat, Toby Bruce said, “Cap’, I hear you are looking for a driver.” Looking up and down, while concentrating on the Homburg, Hemingway replied, “I am, but do you always dress like that?” When he replied, “well…no,” Toby Bruce got the job at sixty-five dollars a month, room and board if wanted, and, according to James McClendon, “all the booze and cigarettes you can stand.” Thus began a relationship that was endeared to Ernest Hemingway for the rest of his life and long after he was gone.

Toby Bruce was a carpenter and cabinet maker, a jack of all trades; he could fix most anything and was at Hemingway’s beck and call as majordomo, chauffeur, factotum, and go-to man. He handled his money, oversaw the remodeling of his houses, and built the first swimming pool in Key West while also building a brick wall around the Whitehead Street house to keep out prying tourists. Toby took care of Hemingway’s boys, took care of his boat, bought his cars, built his bookcases and furniture, hauled his guns and ammunition to and from Cuba, and helped edit and have typed his numerous manuscripts, even designing and drawing the cover of For Whom the Bell Tolls. As a stand-in, he negotiated and closed on Hemingway’s house in Cuba, the Finca Vigia. He shared whiskey with, caroused with, and was beside Ernest Hemingway through three wives, always going with the man. When Hemingway left Pauline and Key West for Cuba and his third wife, Martha Gellhorn, Toby Bruce loaded boxes of manuscripts, guns, and memorabilia and stored them in a back room at Sloppy Joe’s Bar where they remained almost totally forgotten. Later, the priceless items were retrieved after Hemingway’s death by Mary Welsh Hemingway, the three boys…and Toby Bruce.

So, in the end, did the little Arkansas Delta town of Piggott and its most prominent family make an impact on the life, times, and literature of Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Ernest Hemingway, one of the most celebrated novelists of the twentieth century? Say what you want, but it sure made his life and his ability to concentrate on his work, along with what little peace of mind he ever had by knowing Toby Bruce was close by to take care of things, one hell of a lot easier.