By Katie Tims

Hiking the Appalachian Trail might sound easy. But strap on a thirty- to forty-five-pound pack and the game changes. Factor in steep inclines, impossible rocks, slippery tree roots, blaring sun, rain, wind, snow, ticks, bears, snakes, spiders, mud, blisters (lots of blisters), shin splints, twisted ankles, body odor beyond description, and snoring shelter mates.

So why take on the elements, pain, and suffering?

“Because it’s the experience of a lifetime!” John Denton answered. “Once you do the Appalachian Trail, you won’t ever be the same again.” And he means it.

A Few of the Delta’s 2,000-Milers

Every year, an estimated two to three million people hike a little or a lot of the 2,190-mile Appalachian Trail, a footpath that extends from Georgia to Maine. Many start the five-million-step journey; few finish. In fact, since the 1930s, only 20,115 hikers have earned the prestigious 2,000-miler status. These include the “thru-hikers,” who traverse the entire trail in a single season and the “section hikers,” who complete the AT over multiple years.

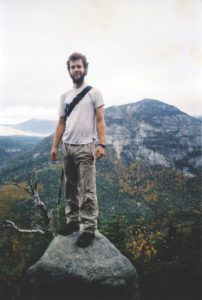

Bay Bennett, twenty-three, is among the thru-hiker class of 2018. Originally from Greenwood, Bennett completed his trek in an impressive four months—starting at Springer Mountain on March 23 and finishing at Mount Katahdin on July 24. As part of his major in outdoor leadership at North Greenville University in South Carolina, Bennett counted the AT thru hike as his internship. He started and finished the AT (as the trail is known) with his friend, Maxx Marshall, who is a dual major in English and music at Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Bay Bennett, twenty-three, is among the thru-hiker class of 2018. Originally from Greenwood, Bennett completed his trek in an impressive four months—starting at Springer Mountain on March 23 and finishing at Mount Katahdin on July 24. As part of his major in outdoor leadership at North Greenville University in South Carolina, Bennett counted the AT thru hike as his internship. He started and finished the AT (as the trail is known) with his friend, Maxx Marshall, who is a dual major in English and music at Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee.

“We love being outside and being on the trail,” Bennett said. “We’re big early birds, so we’d just get up and walk until we got tired. By the end of the trail, twenty-nine miles was a normal day for us.”

Lloyd Caulfield thru hiked in 2003 at the age of twenty-three. He started on April 17 and summited Mount Katahdin on September 30. Prior to the AT, Caulfield’s backpacking experience consisted of walking with a pack eight miles along a highway near his home in Water Valley, Mississippi.

Lloyd Caulfield thru hiked in 2003 at the age of twenty-three. He started on April 17 and summited Mount Katahdin on September 30. Prior to the AT, Caulfield’s backpacking experience consisted of walking with a pack eight miles along a highway near his home in Water Valley, Mississippi.

“The Appalachian Trail is one of those big life-changing events,” Caulfield says. “After you do the Appalachian Trail, you categorize everything in your life as ‘before the trail’ or ‘after the trail.’ The AT leaves an indelible mark on your life.”

Blake Moore was in college when he completed a twenty-eight-day backpacking trip in the Eastern Alaska mountain range as part of the National Outdoor Leadership School. This, in addition to a spring break trip to the Appalachian Trail, was inspiration for a thru hike, which he completed at the age of twenty-six, starting April 12 and finishing Sept 15.

“Thru hiking the AT was something I’d always wanted to do,” Moore explained. “I’d planned on doing it when I graduated from college, but then I went to work as an accountant. The last thing you want to do in a professional career is ask for six months off. But I did it anyway.” (By the way, he was promoted and given a raise while on the trail.)

“Thru hiking the AT was something I’d always wanted to do,” Moore explained. “I’d planned on doing it when I graduated from college, but then I went to work as an accountant. The last thing you want to do in a professional career is ask for six months off. But I did it anyway.” (By the way, he was promoted and given a raise while on the trail.)

John Denton is a farmer in Cleveland who section hiked the AT in just two seasons. Over the 2017 and 2018 summers, at the ages of sixty-five and sixty-six, Denton alternated his time between the trail and the Delta.

“I read about the trail back in the ‘60s—I must have been twelve or thirteen years old,” Denton recalled. “The article was in National Geographic, and I said, ‘One of these days I’m going to do that!’ A few years ago, I thought I better hurry up. I almost waited too long.”

Eighteen-year-old Mary Randal Henson, from Leland, is not yet a 2,000-Miler, but she started the AT on April 17. At this very moment, Henson has her sights set on Mount Katahdin, a goal she’s had since a family vacation four years ago.

“When I was fourteen, we went white water rafting at the Nantahala Outdoor Center in North Carolina,” Henson explained. “The trail goes right through the center. I saw the AT hiker box and the plaque on the wall. Ever since then I’ve wanted to hike the AT. I’ve taken a gap year to do my hike.”

Crux, Thoreau, Bear and Johnny Walker

On a recent Saturday at the Delta Meat Market, three of these 2000-milers and Henson got together. Three hours later, the conversation was still going strong.

“Hey, Bear, what do you think was the hardest part?”

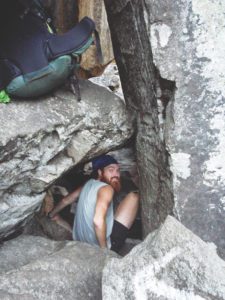

“Mahoosuc Notch, without a doubt,” Bear answered, referring to a tough mile-long section in western Maine. “It’s a valley, and all the rocks have crumbled off the top and piled down into the bottom. Some are as big as a house. You go up the rock, under the rock, around the rock.”

“Yeah, you’re not hiking—you’re crawling,” Johnny Walker chimed in.

“There are places where you have to take off your pack and throw it ahead, then climb up to it,” Thoreau added.

Appalachian Trail hikers don’t know each other by their given names. Instead, they go by trail names, which are usually gifted by fellow hikers according to noticeable habits, hobbies, or peculiarities.

Appalachian Trail hikers don’t know each other by their given names. Instead, they go by trail names, which are usually gifted by fellow hikers according to noticeable habits, hobbies, or peculiarities.

Bay is Crux. He loves rock climbing, and “crux” is term for the most difficult move or sequence of moves during a climb.

“A hiker, Bird Dog, spent the better part of three days trying to give my buddy and me trail names,” Bennett said. “I talked a lot about rocking climbing, so that’s where Crux came from. It was fun to have that moniker.”

Caulfield is Thoreau. The name was the result a literary mix-up.

“I really have no knowledge of Henry David Thoreau—it was my lack of knowledge that got me that name,” he admitted.

Moore is Mississippi Bear because of Ole Miss’s mascot debate of Colonel Reb versus the Black Bear. Although it’s not the reason for his trail name, Moore was quick to recount a bear sighting in the Shenandoahs.

“One day I had my headphones on and was just rocking out the miles,” he said. “I looked over and there was a bear, eating blueberries by the trail. I was like, ‘Hi bear!’ I was so close that I could have touched him.”

Denton, appropriately so, is Johnny Walker—not because he drinks whiskey but because he walks… a lot.

“I started with a group and hiked with them all the way to Virginia,” Denton recalled. “I got off the trail for six weeks and then got back on at Hanover, New Hampshire. I didn’t get across the street before I heard, ‘Hey, Johnny Walker!’ I fell right back in my same bunch.”

At the time of this writing, Henson had yet to earn her trail name.

“I just hope it’s not something weird,” she said with a laugh.

The Big Concerns

“Hike own hike” is the wise advice for hiking the Appalachian Trail. But there are a few concerns that all hikers share on the trail.

Of course, shelter and water top the list. Shelters are dotted along the trail, and most hikers come prepared with ample clothing, sleeping bags, and tents or hammocks. As for water, creeks and springs are plentiful along the AT. On his hike, Moore didn’t filter his water and had no problems. Denton always filtered his. Bennett fell somewhere between the two, which worked fine until one day in New Jersey.

“It was pouring down rain, and we stopped by this little stream where I scooped up the water and drank,” he recalled. “I didn’t think about the water and how it was coming down from a pond. I ended up with giardia and getting super sick.”

As well, his hiking partner was bitten by a non-poisonous snake in Virginia and contracted Lyme disease near Lyme, New Hampshire. Marshall never saw the tick, but knew something was wrong when he experienced extreme fatigue and terrible headaches. Antibiotics and time took care of the disease, but it did make for several days of slow going.

As well, his hiking partner was bitten by a non-poisonous snake in Virginia and contracted Lyme disease near Lyme, New Hampshire. Marshall never saw the tick, but knew something was wrong when he experienced extreme fatigue and terrible headaches. Antibiotics and time took care of the disease, but it did make for several days of slow going.

Minor injuries are to be expected (and hopefully prevented) on the trail. Blisters, sore muscles, fatigued knees, pack rash, and twisted ankles are just part of the fun. Pain and discomfort are constants, so there’s no use in complaining.

“Your clothes never dry out,” Caulfield said. “You’re either wet with sweat or you’re wet with rain, the whole time.”

It’s the major injuries that are most worrisome. Imagine hiking all the way from Georgia to Maine and then having to give up and go home. That almost happened to Denton.

“I usually busted my a** every fifty miles on the trail,” he said. “I got all the way through New Hampshire and the rocks. The trail was finally getting a little easier. I was happy and bumping along when, all of a sudden, I fell hard. I screamed—it hurt so bad. I thought somebody was going to have to carry me out of there.”

Eventually Denton got back up on his feet and hobbled three-tenths of a mile to a shelter.

“I thought I was done,” he admitted. “But the next morning I got up and kept going. I limped the rest of the way—I barely made it up Mount Katahdin.”

Gear, pack weight, and proper footwear are other concerns. Then comes basic sustenance. With five million steps come at least one million thoughts of food.

“There were times when I hallucinated about McDonald’s french fries,” Caulfield confirmed with a laugh.

“I figured out how to eat,” Moore said, explaining that he had to change his diet after losing thirty pounds in the first three weeks of his hike. “It’s all about calories. My goal was to eat ten thousand calories a day. I didn’t always hit that, but it was my goal.”

“I figured out how to eat,” Moore said, explaining that he had to change his diet after losing thirty pounds in the first three weeks of his hike. “It’s all about calories. My goal was to eat ten thousand calories a day. I didn’t always hit that, but it was my goal.”

It’s tough to eat that much without weighing down the pack. So, as THE TREK wisdom dictates, a hiker “should eat as much as possible, whenever possible.” That means making the most of the occasional restaurants, fast-food joints, and gas station stores.

“You gorge yourself as much as you can when you get to town,” Moore advised.

On the trail, hikers must carry high-calorie, low-weight food. A few of the favorites are tuna packets, dried fruit, peanut butter, Cheetos, tortillas, jerky, and dehydrated meals, as well as Pop Tarts, instant oatmeal, Nabs, instant coffee, and Snickers chocolate bars.

“We had brown sugar and cinnamon Pop Tarts every day for breakfast for four months,” Bennett said.

“I think my daily intake was three Snickers bars a day,” Moore added.

“After the trail I couldn’t eat any tuna for years,” Caulfield said.

Memories of a Lifetime

Completing the Appalachian Trail isn’t as much about physical conditioning or prior backpacking experience as it is about raw determination. That was the case for Bennett when he celebrated his twenty-second birthday while hiking through freezing weather and foot-deep snow. It was the same for Denton whose slow pace dictated early starts and late finishes. Moore suffered stress fractures to both shins negotiating a long, steep downhill slope, which resulted in ten days of forced rest.

Completing the Appalachian Trail isn’t as much about physical conditioning or prior backpacking experience as it is about raw determination. That was the case for Bennett when he celebrated his twenty-second birthday while hiking through freezing weather and foot-deep snow. It was the same for Denton whose slow pace dictated early starts and late finishes. Moore suffered stress fractures to both shins negotiating a long, steep downhill slope, which resulted in ten days of forced rest.

Caulfield darn near didn’t make it to day one. His parents dropped him off at Amicalola Falls State Park, and Caulfield planned to spend the night in the shelter. The next morning he would hike the eight-mile, uphill approach trail to Springer Mountain and the southern terminus of the Appalachian Trail.

“It was pouring rain, and I had a 101-degree fever that night,” Caulfield recalled. “I wanted to cry. I wanted to call my parents and say, ‘Come get me! I’m not going to do it.’ But there was no cell service. The only option I had to was to go hike. After that night I never thought about quitting again.”

Yes, there are challenges on the Appalachian Trail. But according to these hikers, the rewards far outweigh the difficulties. Lifelong friendships are made on the trail, bonds that connect people who appreciate the decision to make the arduous 2,200-mile walk.

Moore hiked the second half of the trail with a group of close friends—Team Party, as they called themselves. It’s eleven years later, and they still keep in touch. Caulfield’s experience is similar; he met his group at the very first blaze in Georgia. Trail fellowship knows no genders, no political affiliations or ages.

Moore hiked the second half of the trail with a group of close friends—Team Party, as they called themselves. It’s eleven years later, and they still keep in touch. Caulfield’s experience is similar; he met his group at the very first blaze in Georgia. Trail fellowship knows no genders, no political affiliations or ages.

“You’re all bound by a common goal. Your politics are hiking,” Caulfield said.

Last year, Denton met up with an eighty-year-old thru hiker. “I thought, ‘Man, I’ve found somebody I can hike with because he’s going slow like me.’ We bumped along for a while, then all of a sudden he was like the road runner—beep, beep, ptewwwwww!”

Mindfulness teaches us to live in the present, to notice details and be grateful. On the AT, a hiker’s schedule is cleared by five million steps, one foot in front of the other. There are a lot of mindful moments.

“On the trail I kept having childhood memories—stuff I’d never thought about before,” Denton said. “Maybe that’s the reason I was so slow—my brain was going faster than my feet. You think about stuff you did and some stuff you wish you didn’t do. A lot of people are running away from stuff.”

“On the trail I kept having childhood memories—stuff I’d never thought about before,” Denton said. “Maybe that’s the reason I was so slow—my brain was going faster than my feet. You think about stuff you did and some stuff you wish you didn’t do. A lot of people are running away from stuff.”

“I think I thought about food most of the time,” Caulfield admitted with a chuckle.

“For me, the trail made me live in the moment,” Moore said. “Every day is its own. Don’t take it for granted.”

This led to his advice for Mary Randal Henson, who was about to start her AT thru-hike.

“Don’t worry about next week or six months down the trail. Don’t think about Katahdin when you start because you’ll never get there. It’s just too far away. Just enjoy the journey.”

1 thought on “Trailblazers”

On August 9th, I will embark on my 19th trip to the AT. I started on Klingman’s Dome and hiked south to Fontana Dam with 6 Boy Scouts (one of whom was my son) and a friend in June of 2000. The next summer, my son and a friend of his and I went to Deep Gap, just north of the GA/NC border and hiked north to the Nantahala Outdoor Center. The next, we started at Springer Mt and I have been a NOBO (Northbounder) ever since. This summer, I start in Rangeley ME with an ultimate objective of Monson and plan to finish the Trail next year. Someone once asked me what my favorite section of the Trail was to which I replied there were memorable sections of the Trail for sure. But, what I remember most is the people I met along the way. There are STILL a lot of kind people in this world. Sometimes, you just have to go for a walk to find them.

Gray Fowler

Fat Man Walking

GA-ME 2000-2020