By KATIE TIMS

Modern-day hunter-gatherers of artifacts are helping preserve the Delta’s history

This man walks back a thousand years, almost every day. Out the front door and down a path straight into long ago, John Meek traverses a vast timeline—weather permitting, of course. “In the season I walk eight or ten miles a day, at least,” he says. “I go whenever I can get out and see them in the dirt.”

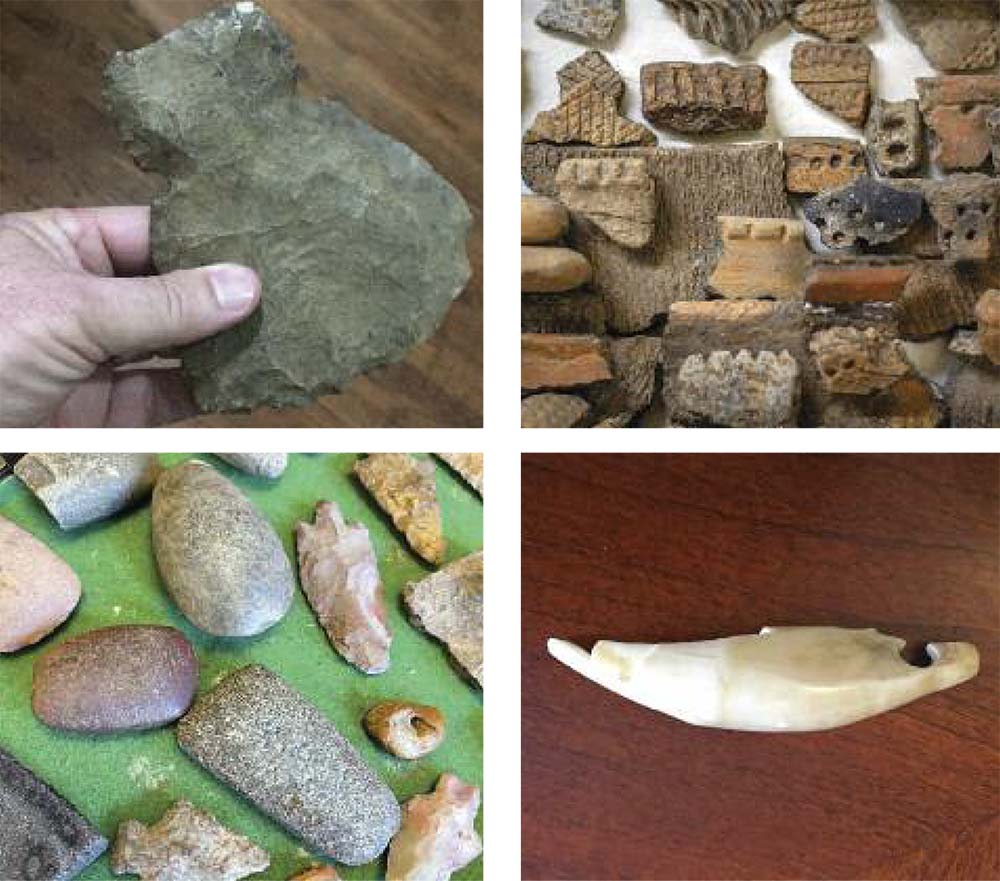

Them: Native American arrowheads, spear points, stone tools, pottery, pipes, beads, bone implements, game pieces, ceremonials, weapons, pendants, and everything required for survival, society, culture.

John paints landscapes, and he travels the backroads of the Delta in search of places to photograph. Along the way, he stops and hunts for Native American artifacts. Fifty years of collecting line the walls of John’s house, a stately century-old structure built on land his family homesteaded along the west bank of the Tallahatchie River almost two hundred years ago. He walks nearby farm fields in search of stone points, pottery, tools, jewelry, game pieces, and other remnants of the Native Americans who inhabited the Mississippi Delta for thousands of years.

A Condensed History

Native Americans lived here for thousands and thousands of years. This was confirmed in the 1990s when geomorphologist Roger Saucier, who worked for the Corps of Engineers, worked with archeologists to accurately date sites in the lower Mississippi River Valley where ancient projectile points were found. Together, they re-wrote conventional wisdom by linking modern geologic mapping with in-the-field discovery.

It’s complicated, but Saucier’s theories rested on the foundation of climate changes, melting glaciers, meandering creeks (referred to as “braided streams”), and the wandering flow of the Mississippi River. Saucier tied geologic features to the abundant presence of Dalton-era projectile points, which were made between 9,900 and ten thousand years ago and found at campsites on the Arkansas side of the lower Mississippi River Valley. Before his work, it was thought those landforms dated somewhere around five thousand years ago. Recent lidar typographical mapping in Mississippi underlined Saucier’s findings—Native Americans lived here at least ten thousand years ago.

“We knew animals were living in the Yazoo Basin—mastodons and other Pleistocene age (this was the transition from the last Ice Age to a warmer climate) animals, and we knew Indians hunted them here because we found their tools,” says Jessica Crawford, archeologist and southeastern director of the Archeology Conservancy, a forty-year-old non-profit organization.” We’ve just never been sure to what extent they lived here. It stands to reason that the more ten-thousand-year-old tools we find, the more it appears they were here. We still don’t know how long they stayed here or what their camps or houses looked like.”

Back then, the Mississippi Delta was covered by lush grass, hardwood trees, and clear running streams. Wildlife, birds, and fish were varied and abundant. The backdrop was ideal for the ancient hunter/gatherer, semi-nomadic bands of people who camped on high sandy terraces near water, moving according to conditions and availability of food sources.

Starting about five thousand years ago, people in the Mississippi Delta became more sedentary and lived in one place for longer. Pottery making, community building, and mound construction began. Then about one thousand years ago, Native Americans began cultivating crops, and that ushered in major changes including larger towns, political organization, tribal formation, societal hierarchy, ceremonies, burials, and advanced tool making.

Explorer Hernando DeSoto arrived in the Mississippi Delta around 1540, thus initiating the Europeans’ first contact with the region’s Native Americans. Waves of Europeans soon followed. At first there was cooperation and trading—mostly, the Indians trading furs and raw materials for the Europeans’ manufactured goods, which included metal objects and beads (items often found among the remains of Native American campsites). Over the next three hundred years, as we know, the Delta’s Native Americans were decimated by disease, warfare (among themselves and in alliance with Europeans), and displacement.

Conserving the Past

And so we arrive back at John Meek’s impressive collection. It’s just one of many in the Mississippi Delta. From the young child with one broken spear point to the museum with an assemblage of the best pieces from multiple collections, there are millions of Native American artifacts floating around in display cases, shelves, buckets, drawers, boxes, barrels, and pockets.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was passed in 1990. It not only protects the graves of Native Americans, but it also stipulates that institutions receiving federal funding—universities and museums, for example—return bones and artifacts associated with burials and ceremonies to the tribes.

As for that broken spear you spotted on the side of the turn row, is it okay to pick it up?

“If you are on private land and you have permission from the landowner, you can pick up and surface collect,” says Crawford. “You can do what you want with your own land, as long as you don’t disturb human remains—whether they’re marked or unmarked. It is also illegal to have funerary objects, meaning grave goods. Anything on county, state, or federal land is off-limits.”

“There are so many sites around here that it’s unreal—there are hundreds, if not thousands,” says Tom Steele, who lives in Cleveland and hunts for artifacts with his wife, Terry.

“Usually, we hunt in the early spring, right after they till the ground,” collector Jimmy Goodman says. “Once you get a rain on it, washing all the little dirt particles away, then things just pop up—like they’re growing.”

Of course, collectors appreciate the beauty of the objects they find. They may also attempt to appreciate the culture of the people who made it. However, unless professional archeologists have the opportunity to identify the age of the artifact, record the location, and perhaps conduct radiocarbon dating, the story is lost. Obviously, there’s no way to research every single piece. But, collectors know when they find something that could be important to piecing together the past.

“If you don’t pick it up, it’s going to get broken and busted—it will be long gone,” says Lee Hazlewood, who has a vast collection of Native American artifacts from the Delta. “There are a lot of collectors out there who appreciate the culture and study it, who share their finds with archeologists. The professionals aren’t going to take stuff away from you. They just want to know what you’ve got, where you found it, and what context it was in.”

In 1999 behind her house near the Tallahatchie River, Crawford found an old spear, known as a “Coldwater” point (10,000 to 11,000 years old). She recorded it with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, and a site number was listed for the find. Also, because the point was so old, it went into the State of Mississippi’s Paleo Indian database. Because of that recording, a researcher from Mississippi State was able to pinpoint the find and contact Crawford.

“He and another paleo Indian expert came to my house, and we went out there. They’ll be back to do some testing soon,” Crawford says. “That’s how it should work—even for a non-professional. You find it, and you record the location and artifacts with the state, and eventually, it may be very helpful.”

Far too often, however, collections are not organized or recorded. Some have been handed down through generations. For those, there is still some scientific value, according to Nikki Mattson, field representative for The Archeology Conservancy.

“Even if these collections don’t have provenience or the context, they can still be used,” she says. “We can’t learn much about how the people lived, but they can still be studied.”

Future Discoveries

Collecting artifacts in the Delta used to be easier, in the days before land leveling and no-till farming. One could spot the high spots, the sandy places, and the darkened soil that signaled former human occupation. Back then, not as many of the historic Native American mounds had been ground down into invisibility.

With so many changes to the landscape, are there still major Native American discoveries to be made in the Mississippi Delta?

“Oh yes!” Crawford answers.

She points to Troyville Earthworks, a Late Woodland period Native American mound complex in Louisiana. Its mounds were leveled and the town of Jonesville built on top.

“I had written off that site,” Crawford says. “But in the 1990s and early 2000s archaeologist Joe Saunders and other archaeologists started looking at archaic mounds and doing soil cores around the town. They found that there are several feet left of the mounds.”

Such was the case at the Carson Mounds in Mississippi, which were occupied from 1200 to 1600 AD. This vast, mile-long complex north of Clarksdale was mapped in 1894, indicating there were seven large mounds, eighty small mounds, and a human-constructed embankment. Five of the seven mounds remain. In the 2000s, land leveling uncovered several human graves, which led to the professional, eleven-year excavation of a small piece near “Mound A.”

Crawford believes there are more places like the Troyville Earthworks and Carson Mounds.

“They’re looking at sites where it looked like mounds were leveled, but geophysical equipment shows that there are actually a few feet left,” she says. “A lot of times Indians would live on a surface for hundreds of years before they built mounds. Sometimes they would bring fill in, level it off, and live on that for a while before they built mounds. Those parts of these sites are left.”

That’s why she remains optimistic.

“We’ve lost a lot, but there’s still a lot left to discover,” she concludes.

Historical Perspective

If you care to learn more about Native Americans in the Mississippi Delta, there are extensive collections on display and experts who are glad to share information. Artifact collections are featured in several museums, including those at universities.

TOMMY GOODMAN and JIMMY GOODMAN

James Goodman worked for the Mississippi Agriculture Department back in the 1950s and in his spare time farmed a small plot of land near his home in Lexington. On trips to the farm, James dropped off his two young sons—Tommy and Jimmy—at a creek to let them play. And that’s where those boys developed a love for Native American artifacts.

“It wasn’t a free-flowing creek,” recalls Jimmy, a pharmacist who lives in Cleveland. “It was more of a ditch with water in it, but it was clean around it. It didn’t look snaky. We played around the edges and waded the water. Sometimes you’d feel something poke your foot. Usually when you dug down in there, you’d find an arrowhead.”

Tommy is a retired architect who lives in Carrolton and is an artist. While living and working in Birmingham, Alabama, he found his most precious Native American treasure—a pendant made from a bear’s tooth—along the Black Warrior River. He also found a Clovis point. As for his Mississippi Delta finds, Tommy’s favorite is a large intact celt (stone, axe-like tool) made out of gorgeous green rock. That was found near Satartia, at a site that in the 1970s was cleared and farmed for the first time.

“It had all these little creeks and streams going through it, so you could find stuff everywhere. I mean it was perfect!” Tommy says. “We’d go over there and come home with so many points that it was not even funny.”

That site has since been replanted with trees, but the Goodmans still search there and at other places in the Delta. Both brothers have expansive collections—cooking stones, celts of all sizes, pottery, jewelry, game pieces, thousands of points, and tools (bone and stone). Jimmy’s favorite piece is a punch made from a deer’s antler.

“I think it’s more exciting now when I find something than when I was a kid,” Jimmy says. “You find so many pieces and ones that are broken, so when you find one that’s in good shape, it’s real exciting.”

JOHN MEEK

“A friend of mine from Birmingham, he was a salesman for a company that sold all the chemicals you can’t pronounce—the ones you see on railroad cars,” John recalls. “He was into arrowhead hunting, and he got me to walking around the Mound Bayou mounds. Then, I had a friend who bought a place down the road that had a big [Native American] site right on the river, and I started finding good stuff. I got it real bad then. That was forty-two years ago.”

John searches for artifacts almost every day and swears his pain-free back is due to so much bending over to pick up stuff. He never tires of the looking.

“You go and go and go and go and not find anything. But hope springs eternal,” he says. “When you finally find that good thing, it’s usually something special. You’ve put all that time, and it’s like it rewards you with a celt or a perfect point.”

And he has plenty of both, plus so, so much more. When asked about his best find, John picks up one point, then a celt, then a discoidal, then another point. Suffice it to say, John has lots of favorites in his massive collection. One of his favorite stories, however, is about a blue quartz point found in two parts, ten years apart.

As for what he plans for the collection, John offers a clear answer.

“I’m going to give it all back to the Indians,” John answers. “I mean, I feel bad about what we did to them. We came down here and ran them off. We took it over, but that’s just the way the world was back then. That’s why when I get too old to keep looking, I want to give it all back.”

TOM AND TERRY STEELE

Tom Steele is a retired electrician who lives in Cleveland with his wife, Terry, who works at the courthouse. Tom used to deer hunt with a buddy who got him interested in looking for Civil War artifacts, which naturally led to searching for Native American pieces. Now, Tom and Terry spend a great deal of their spare time searching and collecting.

“Of course, a lot of people just go out looking for arrowheads, but there’s so much more,” Tom says. “Before that Indian had a had a projectile, they had to have a tool to make it with—there are all kinds of everyday tools they used—scrapers, grinders, fish weights. You find all of that.”

“Tom finds the big stuff, and I find the little stuff,” Terry says with a laugh, as she hands over her large display of tiny, perfect arrowheads. She also found two stones carved into animal shapes—one a wolf (or bear?) and the other most definitely a fish.

Terry is the one who found a smooth black round stone that is believed to be a game piece. It’s so pristine that an expert said it’s “museum quality.” The cream of the Steels’ collection, however, is a triangle-shaped stone object, which is grooved and carved. It is a true treasure. Tom found it three years ago, about two and a half miles west of Cleveland.

“It’s the darnedest thing I’ve ever seen in my life,” Tom says. “I was going across the road trying to catch my dog—he didn’t want to get into the truck and ran over there. And that’s when I spotted the rock out of the corner of my eye. It was mostly covered. I picked it up, and I knew right off that it was something special. It was laying there like God intended me to find it. It was in a place where you don’t find a whole lot, but when you do it’s special.”

LEE HAZLEWOOD

Lee Hazlewood, an attorney from Eupora, has been collecting Native American artifacts in the Delta for about fifty years. His mom was a kindergarten teacher, and she arranged a fieldtrip for her class to a site near Winona where amateur archeologist John Sumner was searching for Native American artifacts. She took Lee, who was ten at the time. He found an arrowhead.

“One of the first ones I picked up was an early archaic beveled hardened point. I thought something was wrong with it because it had the bevels on it,” Hazlewood recalls with a laugh. “Back then I didn’t really know what I was looking for—I shudder to think about what I walked over. Back then you could stop at almost any field in the Delta and find something.”

Hazlewood fell in love with artifact hunting, and the passion hasn’t waned. He’s picked up thousands of projectile points, tools, and jewelry. Among his highlights are a Clovis point (made in the period 13,050 to 12,750 years ago) and a collection of five hundred to six hundred trade beads, many of which he found while crawling on his hands and knees. Those beads range in size from a golf ball down to a pinhead.

Hazlewood’s favorite find is a stone pendant, known as a “gorget,” that he found just off of Highway 49 about twenty years ago. This gorget is flat, elliptical-shaped, and about as big as his hand.

“When I first saw it, I thought it was an old shoe sole,” Hazlewood says. “In these sites you find all kinds of trash, and over the years I’ve seen a bunch of old shoe soles that I thought were gorgets. When I saw this one, I thought it was the same thing. Then I saw where some of the dirt had come out of the hole on one end. Then I knew what I had.”

RUSTY WEST

Rusty West lives in Clarksdale and works for Simplot in Webb. West has found most of his Native American artifacts while at work.

“It started right after I got out of high school,” West says. “My boss and I’d be in the truck, and he’d drop me off out in the field to go check cotton. He would always come back with an arrowhead and be all excited. That kind of got me excited. Eventually, I started finding them too.”

Happenstance turned into something more.

“After a while you get kind of wise to it. If there’s a high spot that’s near water, you’re going to find an arrowhead. If there’s a bayou or a river and there’s a high spot in the field, something is guaranteed.”

Several times, West has found points while in the field with salesmen who never see the opportunity.

“A bunch of Pioneer salesmen and I were out on a field day when we were looking at different varieties,” West recalled. “There were probably about ten of us out there on the turnrow, going from spot to spot. We were all huddled up, and I was in the middle of talking when I looked down and said, ‘Y’all lookie here!’ I picked up a nice arrowhead right in front of everybody.”

The best moment was on an outing near Minter City. West was with a salesman, helping him fix a problem, when he spotted an odd rock. West bent over and picked up what turned out to be a rare discoidal, one perfectly formed and with a drilled hole in the middle. (A discoidal is a round game piece used in the Native American game of chunkey.

“I picked it up right under his feet. He said, ‘Doggone it! You don’t find arrowheads—they find you!’”